Brook by Brook: Portrait Intime. Dir. Simon Brook. 2001. La Tragedie d’Hamlet. Dir. Peter Brook. Perf. Adrian Lester, Shantala Shivalingappa, and Scott Handy. ARTE France Développment. DVD. ARTE France, 2001.

Brook by Brook: Portrait Intime. Dir. Simon Brook. 2001. La Tragedie d’Hamlet. Dir. Peter Brook. Perf. Adrian Lester, Shantala Shivalingappa, and Scott Handy. ARTE France Développment. DVD. ARTE France, 2001.Among the rarest of the rarities—The Holy Grail (or one of the Holy Grails) of Shakespeare production history study—is Peter Brook's 1970 stage production for the Royal Shakespeare Theatre. It was enormously innovative, it changed everything, it influenced everybody, and it's impossible to find. Indeed, knowledge of the actual performance seems almost gnostic—a little like the way people who went to Woodstock (or claim to have gone to Woodstock) speak about that experience.

I just learned that the staging was never filmed in its entirety. Only a few short segments were filmed (by the BBC).

Therefore, we must make do with clips from documentaries on more general topics. For example, Oberon's "I know a bank" speech is available—but (to my knowledge) only in a documentary on Peter Book by Simon Brook (which is itself something like a special feature—a very lengthy special feature—on the DVD of Brook's Hamlet).

I know a bank where the wild thyme blows,Where oxlips and the nodding violet grows,Quite over-canopied with luscious woodbine,With sweet musk-roses and with eglantine:There sleeps Titania sometime of the night,Lull’d in these flowers with dances and delight;And there the snake throws her enamell’d skin,Weed wide enough to wrap a fairy in:And with the juice of this I’ll streak her eyes,And make her full of hateful fantasies. (II.i.249-68)

A Midsummer Night’s Dream: What to Make of Magic. Staging Dreams: Casting and Interpreting Shakespeare. Dir. Perf. 2004. DVD. Films for the Humanities and Sciences, 2004.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream: What to Make of Magic. Staging Dreams: Casting and Interpreting Shakespeare. Dir. Perf. 2004. DVD. Films for the Humanities and Sciences, 2004.This clip is from A Midsummer Night’s Dream: What to Make of Magic, part of the Staging Dreams: Casting and Interpreting Shakespeare series available through Films for the Humanities & Sciences. And you should definitely ask your local library to purchase the DVD.

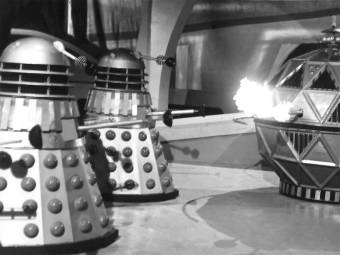

It is a bit of a disappointment that the clips contained in the documentary are so fragmented and so frequently presented without audible dialogue (the narrator's voice is frequently dubbed over the actor's lines). Still, we get a sense of the costumes and the staging here—in some ways, it's better than a gallery of production stills:

Speaking of production stills, Touchstone Exhibitions provides a marvelous resource (even if it is a bit clunky).

“Shakespeare: Drama’s DNA.” Perf. Richard Eyre, Peter Brook, and Judy Dench. Dir. Roger Parsons. Changing Stages: 100 Years of Theatre. Episode 1. BBC. 5 November 2000. Videocassette. Films for the Humanities, 2001.

“Shakespeare: Drama’s DNA.” Perf. Richard Eyre, Peter Brook, and Judy Dench. Dir. Roger Parsons. Changing Stages: 100 Years of Theatre. Episode 1. BBC. 5 November 2000. Videocassette. Films for the Humanities, 2001. I have written a bit on this bit before, but, for the sake of convenience, I'm providing the clip on this post as well.

The clip is from a lengthy documentary series on the development of the stage in England. It's quite well done—but I will always gravitate toward the segments on Shakespeare. In this case, I appreciate the provision of elements from Peter Brook's production:

Click below to purchase Brook by Brook from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

.png)