Palmer, Jim. "In Fair Verona." Ozymandias and Other Stories. St. Louis: Power Publishing, 2004. 29-65.

I got this collection for one reason: The short story "In Fair Verona" and its probable Shakespeare connections. Actually, I got it for two reasons: It's set in St. Louis, one of the greatest cities in the world! Well, all right—I got this book for three reasons. I'm a friend of the author and he gave me a copy.

But we can ignore that third reason as irrelevant because "In Fair Verona" is a very good short story.

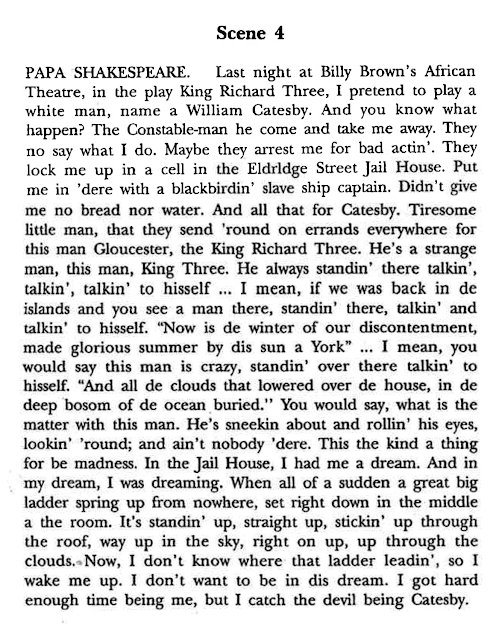

The plot (as you might imagine) has some connection to Romeo and Juliet. But the plot, although interesting, isn't where the interest in the story lies.

The interest is in the vividly-painted immigrant communities (and the individuals that make them up) that Palmer provides us. In "In Fair Verona," we might expect a Romeo-and-Julietesque plot where a man and a woman from two different immigrant communities fall in love despite the disapproval of each community for the other. And the story starts us off with that possibility.

There are Bosnians. There are the Italians down on The Hill (an area of St. Louis still largely populated by the Italian community—where you will find

Viviano's, the single best Italian grocery store in the world—well, in North America at any rate . . . I admit that there may be good Italian groceries in Italy). There are Georgians (not the Jimmy Carter kind; the David Dephy Gogibedashvili kind). And there are many others.

Including the Grussetians.

And that's where the genius of this book makes itself felt most keenly.

The immigrant group called the Grussetians, with Grussetia, the Old Country, and Galaktraish, its capital city, is the center of this collection of stories. And I spent considerable time and energy trying to figure out who, exactly, they were. Alas, when I read beyond the Shakespeare-related short story, this is what I learned: "But nobody knew nothing about us Grussetians" (2).

Still, this immigrant group was so vividly portrayed that I couldn't imagine that it was fictional. I Googled. I asked colleagues. I even sent an e-mail to the author! And I read on in the collection:

We all lived off of where Pestalozzi Street meandered down into the state streets in an area that the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, in a piece on St. Louis's old ethnic neighborhoods, described as "a pocket of recent arrivals from the remote region of the Caucasus mountains called Grussetia." We thought it sounded complimentary, and ever since the article appeared, we had referred to our neighborhood as The Pocket. A lot of homes in The Pocket still had this moldering yellowed newspaper article tacked to the wall years after the Globe-Democrat had shut down and ceased to exist. (2)

I've finally reached the conclusion that the Grussetians are a fictional group. But it's a tribute to the author and the collection that they're painted so remarkably convincingly that they seem utterly real in every detail.

But I now realize that I've been digressing. But it's been worthwhile. This collection is really astonishing. It's something between Stand by Me, My Big Fat Greek Wedding, the stories of Edgar Allan Poe, and (remarkably enough) the Great Brain series.

We would expect a Romeo and Juliet story set in such a community to be a cross-immigrant love story. Instead, it's an intra-immigrant love story (if it even amounts to that).

Within this immigrant community, there are two families (both alike in lack of dignity): The Pantashkivalis and the Oreschtovilis. And in the story "In Fair Verona," a male Pantashkivali impregnated a female Oreschtovili. And the rest of the story addresses the fallout of that. It's not really a question of romance or undying love or whether there's a chemical that will make it appear that you're dead when you're not really dead. It's (first of all) an issue of acknowledging the pregnancy. Here's a quick sample of that part of the story:

Uncle Ingaz is the one person in the community whose word is law. He is, therefore, the one to turn to to settle such complications.

Once I started reading the other stories in the collection, I couldn't stop. Give it a try—it will reward reading. And, actually, you can read the whole "In Fair Verona" here (courtesy of Google Books)!

Click below to purchase the book from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).