Yesterday, I managed to make a road trip to Winona, Minnesota (from the Twin Cities, a drive of just over two hours) to see two plays at The Great River Shakespeare Festival. And I regret nothing.

Every year, The Great River Shakespeare Festival gives the region professional, astounding, life-altering Shakespeare productions of the very highest quality, always rivaling and often superseding the offerings of the nearby metropolitan areas. In short, it is theatre that you should not miss.

Only a few days remain in the season, and they're very close to beating their all-time record for ticket sales. Drop everything and head to one of the shows. If you've never been, they're offering tickets at two for the of one. If you've been before and are bringing a friend who has never been, the same offer applies.

I just have time to make a few notes about the most amazing parts of the productions I saw. These are the points that go above and beyond the baseline of great acting, interesting direction, careful attention to the text, and clear and moving storytelling. These are the transcendent moments The Great River Shakespeare Festival provided.

Hamlet.

I've seen whole handfuls of Hamlets, and I'm always interested in the directors' choices—but I'm not usually surprised by them. In this production, I was delightedly surprised on at least three occasions.

When Hamlet and Horatio have their first exchange, it's generally light, with his "We'll teach you to drink deep ere you depart" delivered very flippantly. Horatio responds much more seriously, breaking through Hamlet's façade of humor with the line "My lord, I came to see your father's funeral." At that point, Hamlet breaks down completely crying on Horatio's shoulder. It was surprising and very effective. We got the sense that there are greater depths to Hamlet's character that only Horatio can unlock. Hamlet staggered on to try to return to a light level with his crack about the funeral baked meats, but now the joke was covering up the pain rather than just a flippant remark.

When the Player King (played to perfection by Jonathan Gillard Daly) delivers his long speech on Hecuba, he paused briefly but significantly after the lines "for, lo! his sword, / Which was declining on the milky head / Of reverend Priam, seem'd i' the air to stick." He glanced ever-so-slightly toward Hamlet, and we got a sense that this was part of Hamlet's problem—that his plan for vengeance is stuck at this point. Again, there was some depth there, and a sense that the Player King knew more than we might expect him to.

When Hamlet comes across Claudius at prayer, he picks up Claudius' own sword as he contemplates dispatching him then and there. Later, he exits with the sword. After Claudius concludes with "My words fly up, my thoughts remain below: / Words without thoughts never to heaven go," he notices the missing sword and looks about for it perplexedly. I don't know whether this was the director's intention or not, but I suddenly wondered whether a biblical allusion was at work. The story of Saul and David in the cave has some intriguing parallels to the scene:

When Saul returned from following the Philistines, he was told, “Behold, David is in the wilderness of Engedi.” Then Saul took three thousand chosen men out of all Israel and went to seek David and his men in front of the Wildgoats' Rocks. And he came to the sheepfolds by the way, where there was a cave, and Saul went in to relieve himself. Now David and his men were sitting in the innermost parts of the cave. And the men of David said to him, “Here is the day of which the Lord said to you, ‘Behold, I will give your enemy into your hand, and you shall do to him as it shall seem good to you.’” Then David arose and stealthily cut off a corner of Saul's robe. And afterward David's heart struck him, because he had cut off a corner of Saul's robe. He said to his men, “The Lord forbid that I should do this thing to my lord, the Lord's anointed, to put out my hand against him, seeing he is the Lord's anointed.” So David persuaded his men with these words and did not permit them to attack Saul. And Saul rose up and left the cave and went on his way. Afterward David also arose and went out of the cave, and called after Saul, “My lord the king!” And when Saul looked behind him, David bowed with his face to the earth and paid homage. And David said to Saul, “Why do you listen to the words of men who say, ‘Behold, David seeks your harm’? Behold, this day your eyes have seen how the Lord gave you today into my hand in the cave. And some told me to kill you, but I spared you. I said, ‘I will not put out my hand against my lord, for he is the Lord's anointed.’ 11 See, my father, see the corner of your robe in my hand. For by the fact that I cut off the corner of your robe and did not kill you, you may know and see that there is no wrong or treason in my hands. I have not sinned against you, though you hunt my life to take it.” (1 Samuel 24:1-11)

I find the possibilities there very interesting. David doesn't take Saul's life out of respect for the Lord's anointed; Hamlet doesn't take Claudius' life out of disrespect for the usurper. That moment along has given me much food for thought.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead.

This was a remarkable production. I can't enumerate the points that were done so brilliantly—there were just too many of them—but the best thing about the production (besides the incredible harmony of the acting pair of Doug Scholz-Carlson and Christopher Gerson) was its pacing. Unlike every other production of the play I've seen, this one deals with the material with a light, fast touch. It's perfect. The audience gets everything—it's enunciated clearly and played with dazzlingly deft blows of language—but nothing gets bogged down. As a result, the mix of humor and philosophy comes through much more powerfully.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead.

This was a remarkable production. I can't enumerate the points that were done so brilliantly—there were just too many of them—but the best thing about the production (besides the incredible harmony of the acting pair of Doug Scholz-Carlson and Christopher Gerson) was its pacing. Unlike every other production of the play I've seen, this one deals with the material with a light, fast touch. It's perfect. The audience gets everything—it's enunciated clearly and played with dazzlingly deft blows of language—but nothing gets bogged down. As a result, the mix of humor and philosophy comes through much more powerfully.

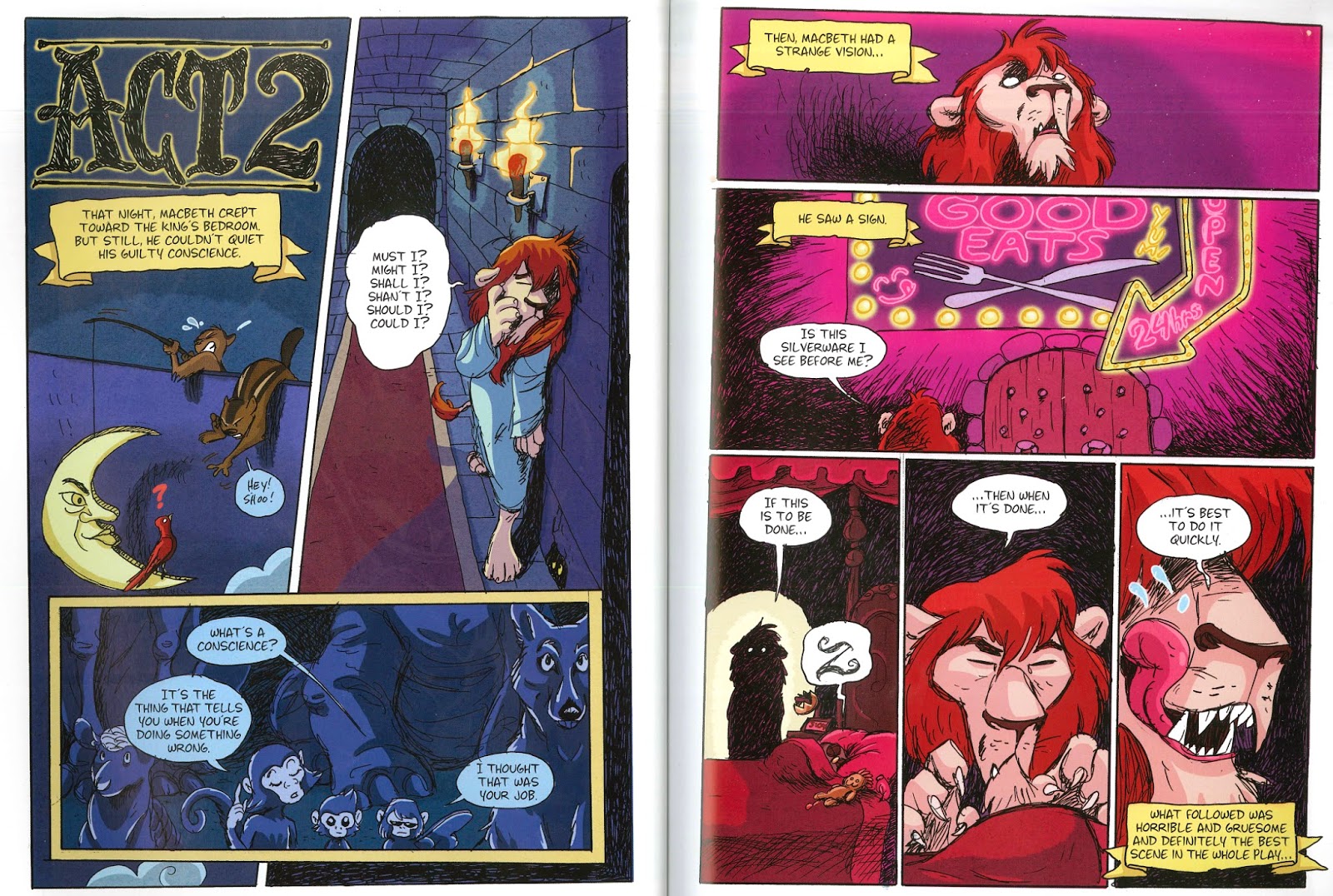

Additionally, the Great River Shakespeare Fest, year after year, produces high-quality videos related to its productions. These are, without exception, remarkable, interesting, humorous, and serious. Witness, for example, "Kids Explain Shakespeare's Hamlet":

If you're anywhere near Winona, Minnesota—by which I mean within a roughly three hundred mile radius—it is completely worth heading to The Great River Shakespeare Festival. Go there. Go there now.