The True Story of Mrs. Shakespeare's Life. Boston: Loring, n.d. [1870.]

The True Story of Mrs. Shakespeare's Life. Boston: Loring, n.d. [1870.]

In addition to more standard Shakespeare fare, I've read a few bizarre things over the past semester and into the summer.

One of those was

The True Story of Mrs. Shakespeare's Life, a book mentioned in

Imagining Shakespeare's Wife (for which,

q.v.) as being "likely written by American Harriet Beecher Stowe" (110).

All I knew about the work before I started reading it came from page 110 of

Imagining Shakespeare's Wife. Here's what that work says:

I found a copy on Amazon (only later realizing that it was one of those "bound copies of freely available .pdf versions of out-of-print, out-of-copyright" books), discovered it was, at twenty-three large-print pages, more of a pamphlet than a major work, and settled down to read it.

Then I discovered that it was a rambling narrative, incoherent at times, about the writer's "venerable ancestor and namesake, Mistress H— B. Cherstow" (17) and her knowledge of the relationship between Anne and William Shakespeare. It's the sort of thing you might hear from the guy at the end of the bar who has clearly had one or two over the eight and who holds some unorthodox views on Shakespeare (or perhaps from someone who corners you at the end of the reception on the opening night of the Shakespeare Association of America Convention).

I didn't understand it at all. Shakespeare was a mass murderer? He lured rival playwrights to Stratford, killed them, and buried them under the famous Mulberry tree? And not just metaphorically but literally? And the evidence is drawn from (1) the writer's ancestor's conversation with Anne Shakespeare shortly before her (Anne's) death and (2) various quotes from Shakespeare about blood and death and murder?

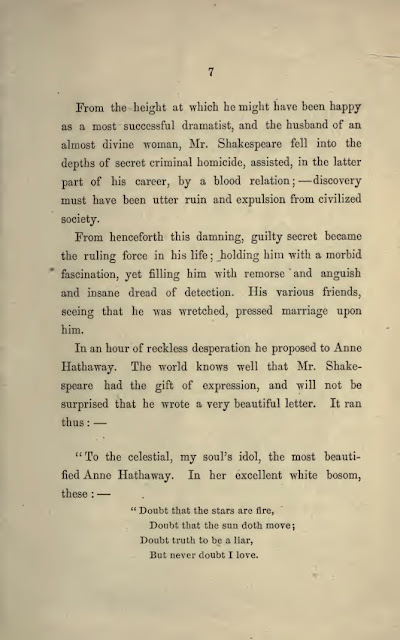

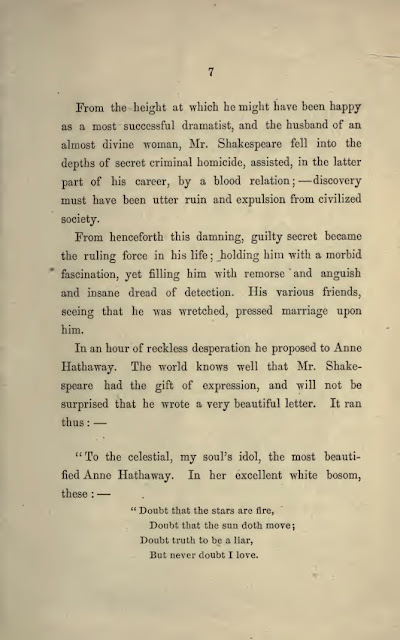

Before we go forward, here's a representative sample of the work:

The author has some very bizarre ideas and is inclined to take every word of Shakespeare as autobiographical (including the great letter from Will to Anne that later makes its way into Hamlet).

Was this Harriet Beecher Stowe having flipped her lid? Was she humorously imagining or seriously imagining an ancestor named H— B. Cherstow (say it fast--you'll get it)? Or was there something else going on of which I was in no wise aware?

After a bit more research, I discovered that what I was reading was actually a parody of a work by Harriet Beecher Stowe, not a work by Harriet Beecher Stowe herself.

In a work published in The Atlantic in 1868 (and, later, in a full-length work entitled Lady Byron Vindicated), Stowe had tried to argue that Lady Byron's estrangement from George Gordon, Lord Byron was predicated on the scandalous behavior of her husband and that she was the patient, long-suffering wife.

A chapter called "Stowe, Byron, and the Art of Scandal" in Susan M. Ryan's The Moral Economies of American Authorship: Reputation, Scandal, and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Marketplace is one of the clearest accounts of the work:

With that information in mind, the bizarre arguments of The True Story of Mrs. Shakespeare's Life fall into place. No one is seriously attempting to create an Anne Shakespeare who is an accessory to her husband's multiple mulberry murders. Someone is parodying Stowe's attempt to re-read the character of Lady Byron through the works of Lord Byron and through unverified conversations.

I'm glad to have gone through the process of confusion, disbelief, denial, bargaining, and acceptance to figure out exactly what this work was all about. Without the knowledge that we're dealing with a parody, it would be the equivalent of taking Allan Sherman's "Automation" as the definitive work on computer development in the latter half of the twentieth century.

Click below to purchase the book from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

Or click here just to download a .pdf for yourself at no charge.

Works Cited

Ryan, Susan M. The Moral Economies of American Authorship: Reputation, Scandal, and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Marketplace. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Scheil, Katherine West. Imagining Shakespeare's Wife: The Afterlife of Anne Hathaway. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

The True Story of Mrs. Shakespeare's Life. Boston: Loring, n.d. [1870.]

Haig, Matt. How to Stop Time. New York: Penguin Books, 2019.

Haig, Matt. How to Stop Time. New York: Penguin Books, 2019.