Trease, Geoffrey. Cue for Treason. New York: Vanguard Press, n.d. [written in 1940; this edition—the fourth printing, printed in the U.S.A. by H. Wolff, New York—1941].

Cue for Treason is a Shakespeare-related Young Adult Novel

avant la lettre. I enjoyed reading it in 2022; I imagine readers in 1940 enjoyed it as well.

I tracked this down because of the Shakespeare connection—by which, I mean the biographical connection to Shakespeare. Shakespeare is a character in the book, and I wanted to see how he was characterized.

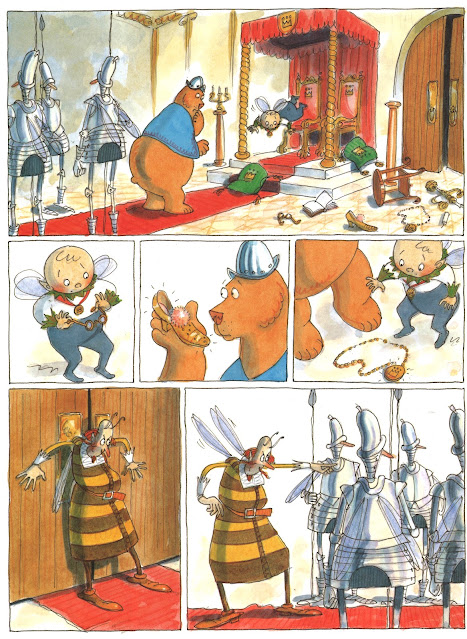

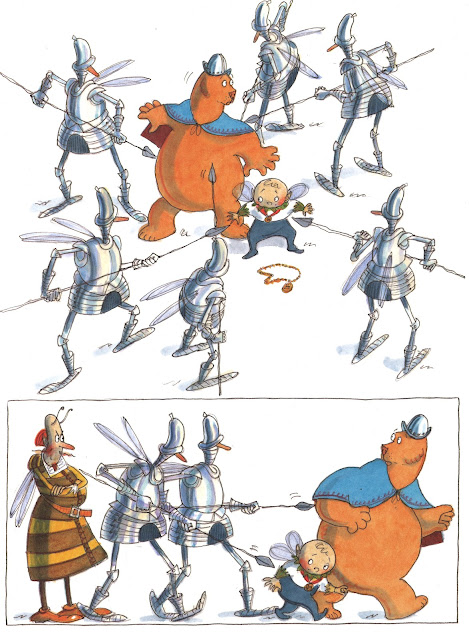

The plot involves Peter Brownrigg, a young boy who runs away from his village because he threw a rock at Sir Philip Morton, a local landowner who is enclosing the traditional village grazing grounds, and fears execution. He meets up with a troupe of traveling players (who are putting on Richard III), and he hides in a box backstage. It turns out the box is the prop coffin that represents the corpse of Henry VI, and it's brought onstage just when Sir Philip's men are searching backstage.

Soon, he's on he way with the friendly troupe. He has some skill in singing, so he's made a player. The troupe encounters another search party, and Peter is found! But the search party doesn't care. It turns out that they're searching for a young woman who has run away because she was being forced to marry someone she doesn't like. [Spoiler (but probably not a very big one): The man in question is Sir Philip!]

Soon, another young boy asks to join the troupe. He's very good at playing the female roles, so he's hired (and this makes Peter very jealous).

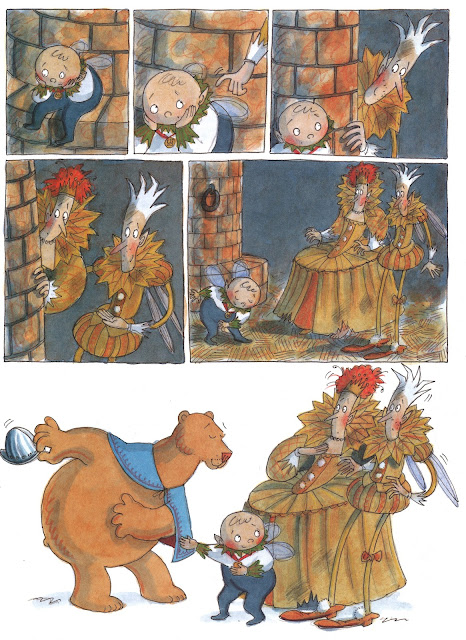

[Spoiler (again, you probably saw this coming): He (going under the name Kit Kirkstone) turns out to be She—the young woman who ran away. Her name is Katharine Russel, and she goes by Kit whether people think she's a boy or a girl.

Hijinks Ensue.

My interest in starting the book was to find out what Shakespeare's character was like, so let me give you a sample of that portion (from which you can also glean the quality of the writing and the level of attention to historical detail). The two new members of the acting troupe don't meet him until they get to London, but here's what happens when they do (I'm giving you the end of the chapter where they realize that the kind man they've been talking to is Shakespeare himself and the beginning of the next chapter):

And now we'll jump to the next chapter, but not before I fill in the plot! In the rest of that chapter, Kit is ready to debut as Juliet . . . until she suddenly panics and runs away. Peter has to take on the role, and his nervousness about it only increases when he sees his enemy Sir Philip in the audience! But Sir Philip doesn't recognize him—partly because he's able to imitate Kit imitating Juliet so well.

I'm giving you the entirety of the next chapter, but if you want to jump straight to the Shakespeare part, you can start with the last line on page 112.

Shakespeare is portrayed in a significantly sympathetic light. He's a man with greater-than-normal insight into the human condition.

My interest in the novel started with its portrayal of Shakespeare, but it didn't stop there. I was completely caught up in the rest of the plot, in which Peter and Kit are intent on tracking down a manuscript of Henry V that was stolen from Peter. In their attempt to get it back, they learn of a plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth.

Suspenseful Adventures (à la Treasure Island) Ensue.

I won't tell you more about the plot, but I will tell you that I tore through the rest of the book to see where our protagonists would end up and whether Queen Elizabeth I would be safe.

The book reminds me of the Shakespeare's Spy series by Gary Blackwood—which I'm just now realizing I never wrote about on this blog! I'll rectify that soon.

In the meantime, track down a copy of Cue for Treason and read it yourself—or recommend it to your favorite high schooler who likes Shakespeare. Better yet, be that high schooler who likes Shakespeare, and read this book!

Click below to purchase the book from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

Note: The one on the left is expensive; the one on the right considerably cheaper.

Additional Note: I was temped to call this post "Cue Trease on

Cue for Treason." You know—because of the author's last name.