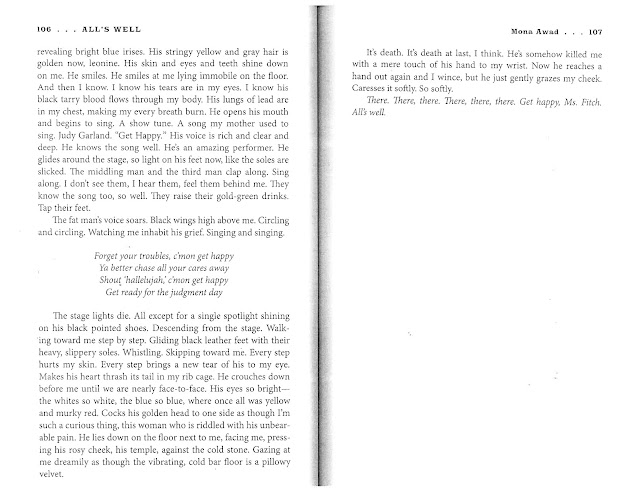

Shakespeare, William. King Lear. Ed. R. A. Foakes. Arden Shakespeare. London: Routledge, 1997.

I'm very fond of the

Chop Bard podcast. Ehren Ziegler, its host, has thoroughly and entertainingly examined at least eighteen Shakespeare plays over the course of 224 episodes. It's been a while, but

Episode 153: "The Difference of Man" featured some commentary I wrote in to the show. You can listen to a portion of that in that episode (the comments start at 1:20), but I wanted to share those points and others here (expanded and slightly edited and illustrated) as well. Here, then, is a large part of what I wrote.

Dear Ehren:

In

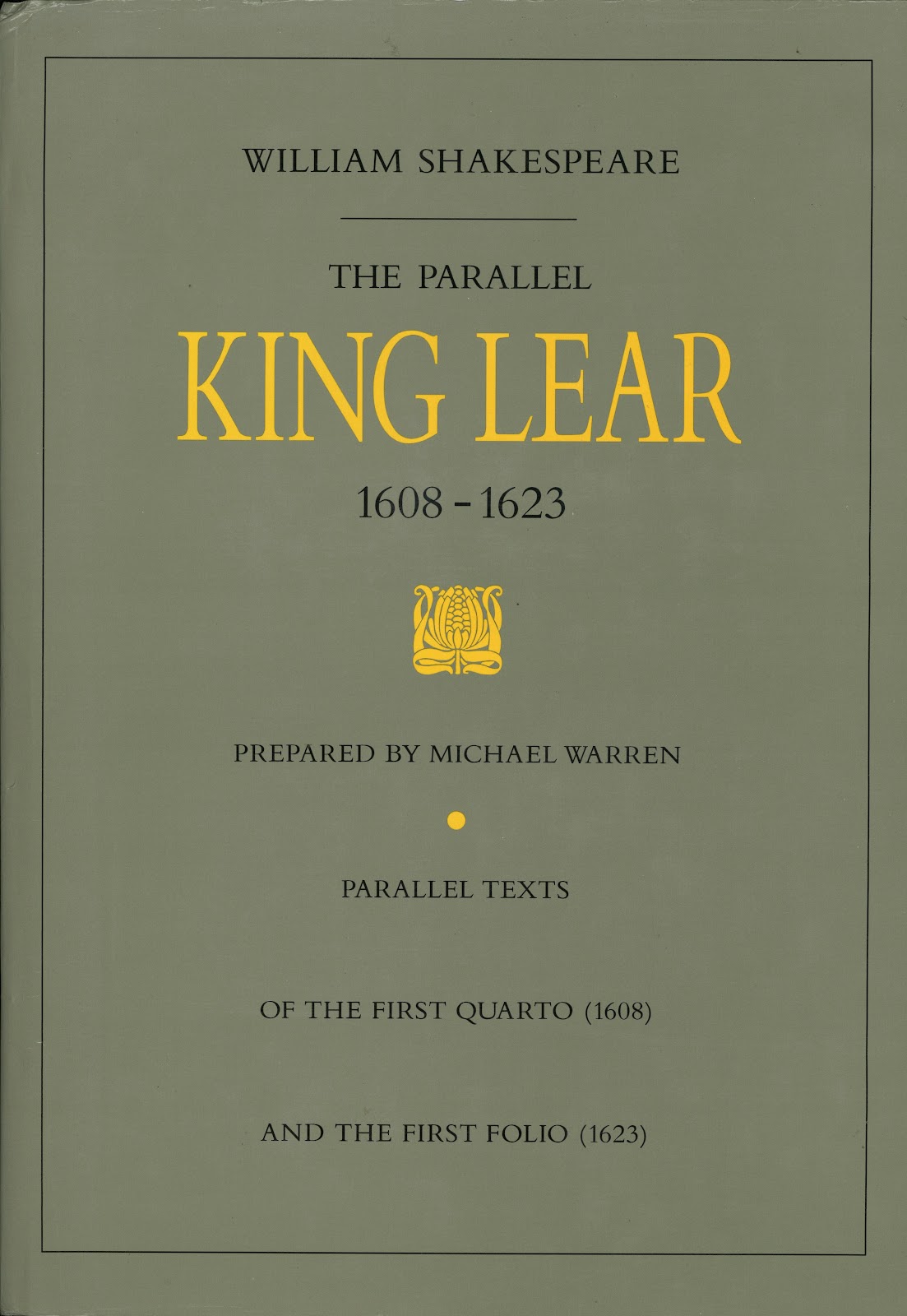

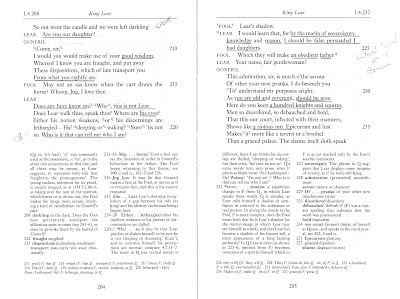

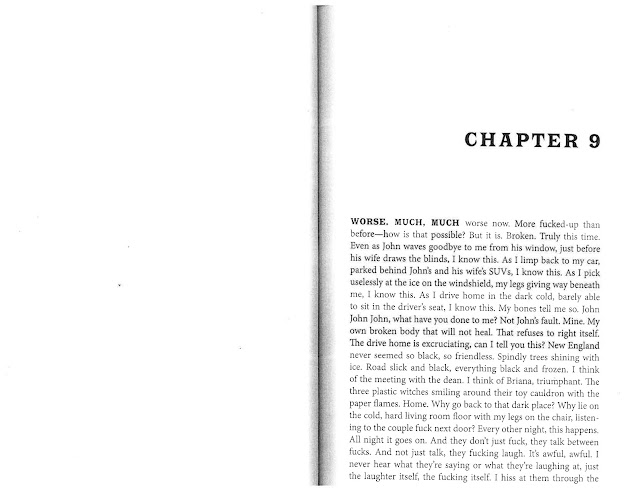

Episode 144 (“Serpent’s Tooth”), you provided a fascinating account of the wealth of interpretative possibilities available in the line “Lear’s shadow” (I.iv.222 in the Arden edition—see the image above). The line immediately before that line is one of immense significance: “Who is it that can tell me who I am?” (I.iv.221). When Shakespeare uses phrases like “I am,” he’s usually getting at something important. And when he breaks the language up into pure monosyllables, it slows up the language, forcing us to pay additional attention to the line. The line then becomes—especially in F, where it’s printed as blank verse (see the image below from

The Parallel King Lear—for more on that volume,

q.v.)—a cry for clarification of his identity, which has deteriorated quite a bit already.

The line “Lear’s shadow” is spoken by Lear in the first quarto and by the Fool in the first folio (see the same image above). As I recall, you gave the following remarkable possibilities for the line as spoken by the Fool in F.

- Lear’s shadow (his actual shadow) could tell Lear who he is—and, since it can say nothing, the answer is “nothing.”

- Lear’s shadow (the Fool) could tell Lear who he is . . . and he’s been trying to all along: “thou art nothing” (I.iv.184-85).

- “Lear’s shadow” is the answer to the question. You’re only the shadow of your former self.

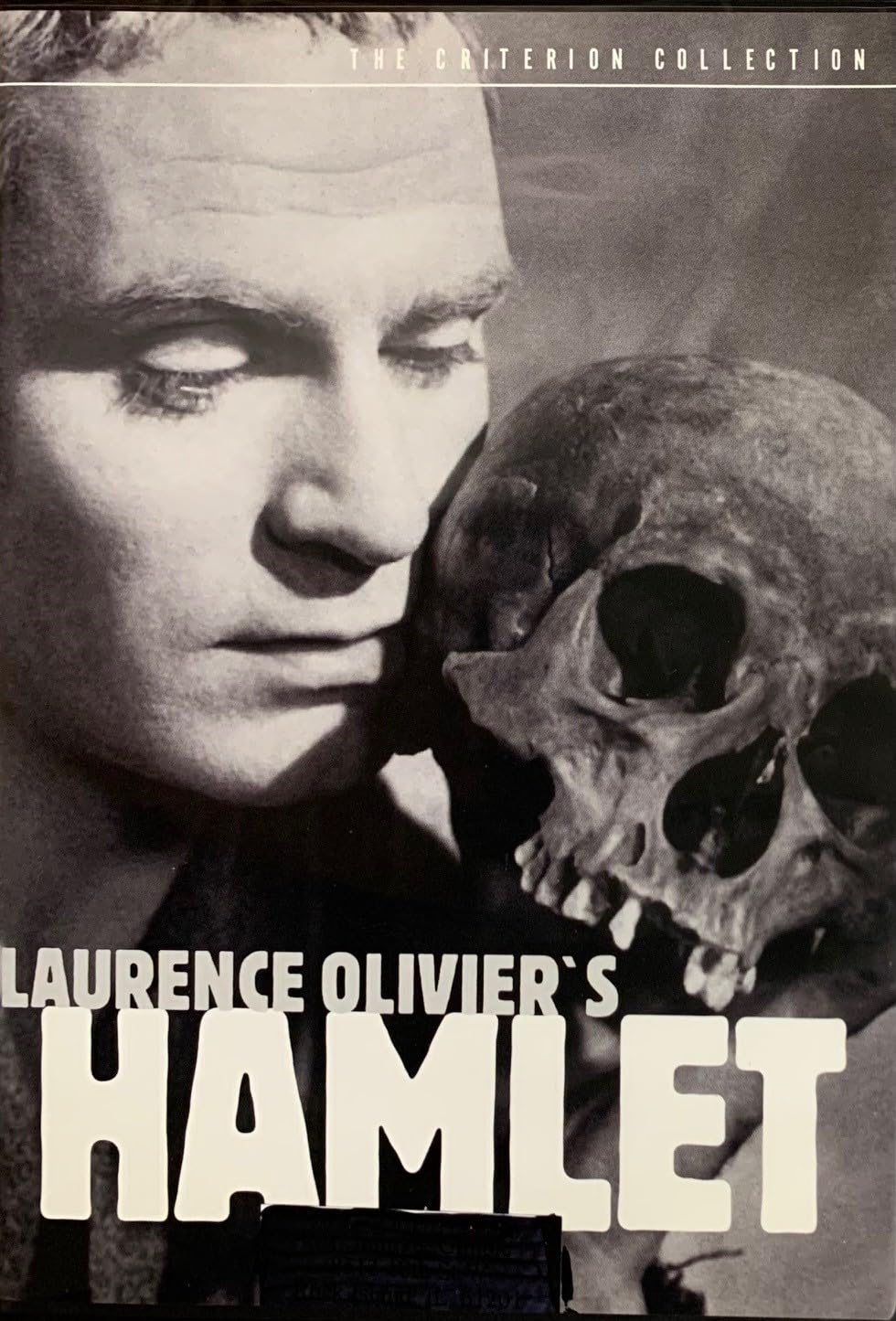

I’d just like to addd one more possible layer of meaning to the line: an intriguingly metatheatrical one.

In Shakespeare’s day, the word “shadow” could mean “player” or “actor.” OED def. 6 b. says, “Applied rhetorically to a portrait as contrasted with the original; also to an actor or a play in contrast with the reality represented.” It cites “If we shadows have offended” and "The best in this kind are but shadows” from Midsummer Night’s Dream and "To your shadow, will I make true love” from Two Gentlemen of Verona:

This provides the possibility for the line meaning “the actor playing King Lear” in addition to all the other polysemous meanings that are running around the line. As an inside joke, it’s intriguing. It’s like all those times in Agatha Christie novels where the characters say, “If this weren’t actually happening to me, I wouldn’t believe it—I would think I was in a mystery novel.” It calls attention to the fact that we’re watching a play while still enabling us to be intensely caught up in the lives of the characters. This is especially the case in Q1, where Lear speaks the line. There, it would mean, in one rough sense at least, “Who am I? Just some guy playing the role of King Lear?”

The other point about that episode that I’d like to bring to your attention is this exchange between Lear and the Fool:

Lear: Dost thou call me fool, boy?

Fool: All thy other titles thou hast given away; that thou was born with. (I.iv.141-43)

The way you read the line was intriguing. You read it as if there were no punctuation: “All thy other titles thou hast given away that thou was born with.” Rephrasing this to maintain that grammar, we get “All thy other titles that thou was born with thou hast given away.” With the semi-colon, it amounts to “You’ve given away all your titles except the title you were born with, and that title is ‘fool’” (i.e., "All thy other titles thou hast given away; that [the title of fool] thou was born with”). Your reading shifts the emphasis from having the title of fool to giving away all other titles, and that’s an interesting alternate emphasis. Well done! [Note: That line is only in Q, where it is printed with a comma and a capital T for Titles: “All thy other Titles thou hast given away, that thou was born with.” Additional Note: Jacobean punctuation is fluid enough for that comma to represent either a semi-colon or a slight pause.]

Finally, I’d like to point you toward a line you’ll get to in the next episode. At the end of Edgar’s speech where he starts to try out the role of Poor Tom, he gives another one of Shakespeare’s “I am” lines, but with a fabulous twist. Edgar concludes his speech with “Edgar I nothing am” (II.ii.192). I always ask my students (particularly those who are taking the advanced grammar class we offer) to diagram that sentence, and they almost always turn it into something like “I, Edgar, am nothing”—which is probably grammatically accurate, but it doesn’t actually account for everything packed into that line. The use of the word “nothing” that’s been running through the play is called back here again—Shakespeare loves to ring changes on different words!—and that, together with the arrangement of the words, gives us much to ponder. It seems that Edgar means something more like “As Edgar, I’m nothing, but I can at least be something if I’m Poor Tom” or “Edgar has become nothing,” implying that Edgar is emptied of all that gave him identity when he heads out to the heath with this new identity.

Those are thoughts that just a few lines of

King Lear inspire in me every time I read the play. Themes of identity, nothingness, and foolishness are caught up in complicated ways that make me marvel every single time.