Until about a month ago, I had no idea that the screenplay for Kenneth Branagh's full-text Hamlet was available. Since it's been available since the film was screened in 1996, that's quite an oversight! But I was very happy to rectify it.

The screenplay itself is interesting for its stage directions. For example, we learn that the opening sequence begins this way:

Darkness. Uneasy silence. The deep of a Winter's Night. A huge plinth, with the screen-filling legend carved deep in the stone, HAMLET. The Camera creeping, like an animal, pans left to reveal, a hundred yards away, ELSINORE, a gorgeous Winter Palace. Effortlessly elegant, yet powerful in its coat of snow. (1)

Branagh's introduction is interesting in providing some biographical background to his interest in Shakespeare in general and Hamlet in particular. In it, we get these memorable statements:

The screenplay is what one might call the "verbal storyboard." An inflexion of a subjective view of the play which has developed over the years. Its intention was to be both personal, with enormous attention paid | to the intimate relations between the characters, and at the same time epic, with a sense of the country at large and of a dynasty in decay. (xiv-xv)

That I should have pursued the play's mysteries so assiduously over twenty years continues to puzzle me. But it's what I do, and this is what I've done. As the great soccer manager Bill Shankly once said, describing the importance of football, "It's not a matter of life and death. It's much more important than that." Certainly for me, an ongoing relationship to this kind of poetry and this kind of mind is a necessary part of an attempt to be civilized. I am profoundly grateful for the opportunity to explore it. (xv)

Both those selections were written before the film was completed, let alone released. I imagine that most viewers see much more of the epic than the personal. But most viewers probably get a sense of the fulfillment of years of thinking about the play in the making of this film.

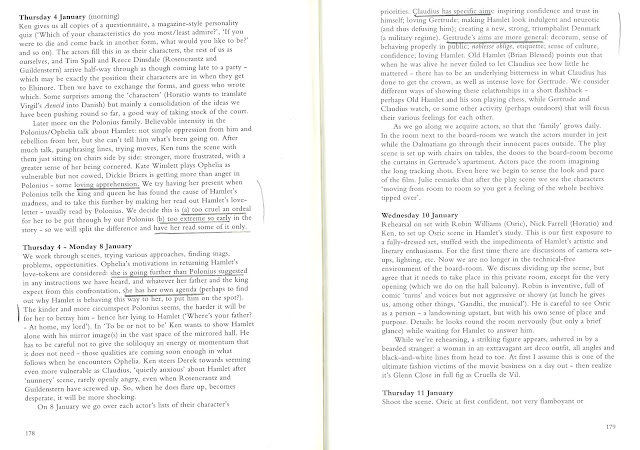

Most interesting to me were parts of the film diary by Russel Jackson. The comings and goings of some enormously famous actors may appeal more to others than to me—they're there if you like that sort of thing. But there's a lot about the process of interpretation. I'd like to give you a couple points of significance there. The first (the marked-up section on the image below) shows us the production's ideas (at least before filming) of some of the connections. It asserts that Polonius has been promoted by Claudius to his position, which may not be too unusual a position (though the text is silent on the issue). But it also says that Hamlet and Ophelia have been having an affair . . . notably "since the death of Hamlet senior" (177). In this production, their affair has lasted, therefore, only two months—nay, not so much, not two. Here's the spread from the book:

I'm not convinced it's a good decision, but it's really wonderful to see how the wheels of the brains were turning in considering it.

On the next spread, we get more on Ophelia's role. At the end of the 4 January entry, we see why they include Ophelia in the scene where Polonius brings the news of Hamlet's connection to Ophelia to Gertrude and Claudius. In the 4 to 8 January section, we get a very interesting question opened. Is Ophelia the one who decides to return Hamlet's "remembrances"? If so, what is the significance of her making that decision?

When they're filming the nunnery scene later (in the 8 March entry), the question comes up again. It's suggested that her returning the remembrances is "from the heart—or at least is what she is trying to convince herself of" (198):

That's a question well worth exploring. I'll need the summer to think about it, but I'll be ready when my Shakespeare class starts in the fall. My impression has been that Polonius (who has been given at least one letter from Hamlet to Ophelia by Act II, scene ii) has demanded / orchestrated / suggested returning the remembrances. This is one thing she says at that point:

Take these again, for to the noble mind

Rich gifts wax poor when givers prove unkind. (III.i.99-100)

It's in no way direct textual evidence to support the claim that Polonius is behind the return of the remembrances, but the rhymed couplet there sounds much more like something Polonius would say than something Ophelia would say. The only other rhymed couplet she utters is at the end of this scene: ". . . O, woe is me / T'have seen what I have seen, see what I see!" (III.i.160-61).

The other interesting thing about the diary in general and that spread in particular is the number of ideas that are eventually dropped. On the right-hand side of that spread, we learn that, at one point, Claudius would be confessing to an actual priest—except it wouldn't be an actual priest. It would be Hamlet in disguise as a priest!

It's probably better that that idea was abandoned.

But I wish that an idea of the gravediggers had made it in. One of them suggested that they start tossing a coin somewhere in the background—bringing a little of Tom Stoppard's Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead into the picture (194).

This book is a great resource for thinking about the play and for working through some details of Branagh's film of it. If only I'd known about it twenty-five years ago . . .

No comments:

Post a Comment