Selznick, Brian. The Invention of Hugo Cabret. New York: Scholastic Press, 2007.

Selznick, Brian. The Invention of Hugo Cabret. New York: Scholastic Press, 2007.

Hugo. Dir. Martin Scorsese. Perf. Asa Butterfield, Chloë Grace Moretz, and Christopher Lee. 2011. DVD. Paramount Studios , 2012.

I have been wanting to write on this book since it came out, but I never seem to have time to sit down and write about it—except when I'm giving an exam. I don't think it's fair to grade other exams while students are taking an exam of their own (all that red ink tends to make them nauseous), but I can write without bothering them too much.

I've read the book

The Invention of Hugo Cabret, and I've seen the film

Hugo based on it, and they're both marvelous—but the book is much better than the film.

Hugo is directed by Martin Scorsese. Like all Scorsese films, it's beautiful. Also like all Scorsese films, it's about a third too long. Some judicious editing would genuinely help the film—even though its acting, its cinematography, and its

mis en scene are all quite marvelous.

Those of you who have read the book or seen the film are wondering where the Shakespeare is to be found. And that's why I'm here. The film's plot revolves around the re-discovery of one of the early makers of silent film: George Méliès. One of his most famous films—both before the writing of the book and the producing of the film and even more certainly now—is

Le Voyage dans la Lune (

A Trip to the Moon). But Méliès also directed a number of Shakespeare films—most unfortunately, none of his Shakespeare films is extant.

However, we do have some detailed descriptions of some of Méliès' Shakespeare films, and the marvelous work

Shakespeare on Silent Film by Robert Hamilton Ball provides some of them. For example, Gaston Méliès (George Méliès' brother) wrote this self-promotional description of George Méliès'

Hamlet (1907), which had a complete run time of ten minutes:

The melancholy disposition of the young prince is demonstrated to good advantage in the grave-yard scene where the diggers are interrupted in their weird pastime of joshing among the tombstones by the appearance of Hamlet and his friend. After questioning them he picks up one of the skulls about a newly-dug grave, and is told that it is the skull of a certain Yorick who was known to Hamlet in his natural life. Hamlet slowly takes up the skull, and his manner strongly indicates, "Alas, poor York, I knew him well!" The following scenes combine to show the high state of dementia of the young prince's mentality. He is seen in his room where he is continually annoyed and excited by apparitions which taunt him in their weirdness and add bitterness to his troubled brain. He attempts to grasp them but in vain, and he falls to brooding. Now is shown the scene in which he meets the ghost of his father and is told to take vengeance on the reigning monarch, his uncle; but not content with this, Hamlet's fates tantalize him further by sending into his presence the ghost of his departed sweetheart, Ophelia. He attempts to embrace her as she throws flowers to him from a garland on her brow, but his efforts are futile; and when he sees the apparition fall to the ground, he, too swoons away, and is thus found by several courtiers. He is raving mad and storms about in a manner entirely unintelligible to them; but they calm him gradually. The last scene shows the duel before the King, when Hamlet returns from the fool's errand upon which his royal uncle had sent him in order to get rid of him. The word is passed, and the well-known story of the duel before the King takes place in pictures which show the Prince's antagonist as he falls after a fierce combat. Now the episode of the poisoned drink, which the King has prepared for Hamlet, is depicted; his villainous mother takes the drink instead, and falls lifeless. Hamlet is now desperate, and bidding the courtiers to stand aside, he ends the life of his wicked uncle with one thrust of his sword, and then turns the weapon on himself; before dying he tells the secret of his terrible enmity toward the King, then sinks to the ground. Lying upon his shield, he is carried off on the shoulders of the courtiers. (Ball 34-35)

To see all that in the inimitable style of Méliès would be beyond the dreams of avarice! And to get all that into ten minutes of screen time would be incomparable. Perhaps Scorsese could learn something from Méliès about streamlining a film.

Brian Selznek's book combines drawings from Méliès' films with contemporary photographs of Méliès, giving his book something of the flavor of the material with which he's working:

I wish I could provide Méliès'

Hamlet, but, at present, we can only hope that it will be re-discovered some day. I can provide a link to one of my favorite Méliès films—with it, your imaginations may be able to re-create something like Méliès'

Hamlet in your mind.

Here, then, is

L'Homme Orchestra (that title could be translated, essentially, as "One-Man Band")—a film from 1900:

Works Cited

Ball, Robert Hamilton.

Shakespeare on Silent Film: A Strange Eventful History. New York: Theater Arts Books, 1968.

Links: The Film at IMDB.

Click below to purchase the book and then the film

(in that order, please—no exceptions)

from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

You may also wish to purchase Shakespeare on Silent Film. If you do, you can start that process by clicking on the link below:

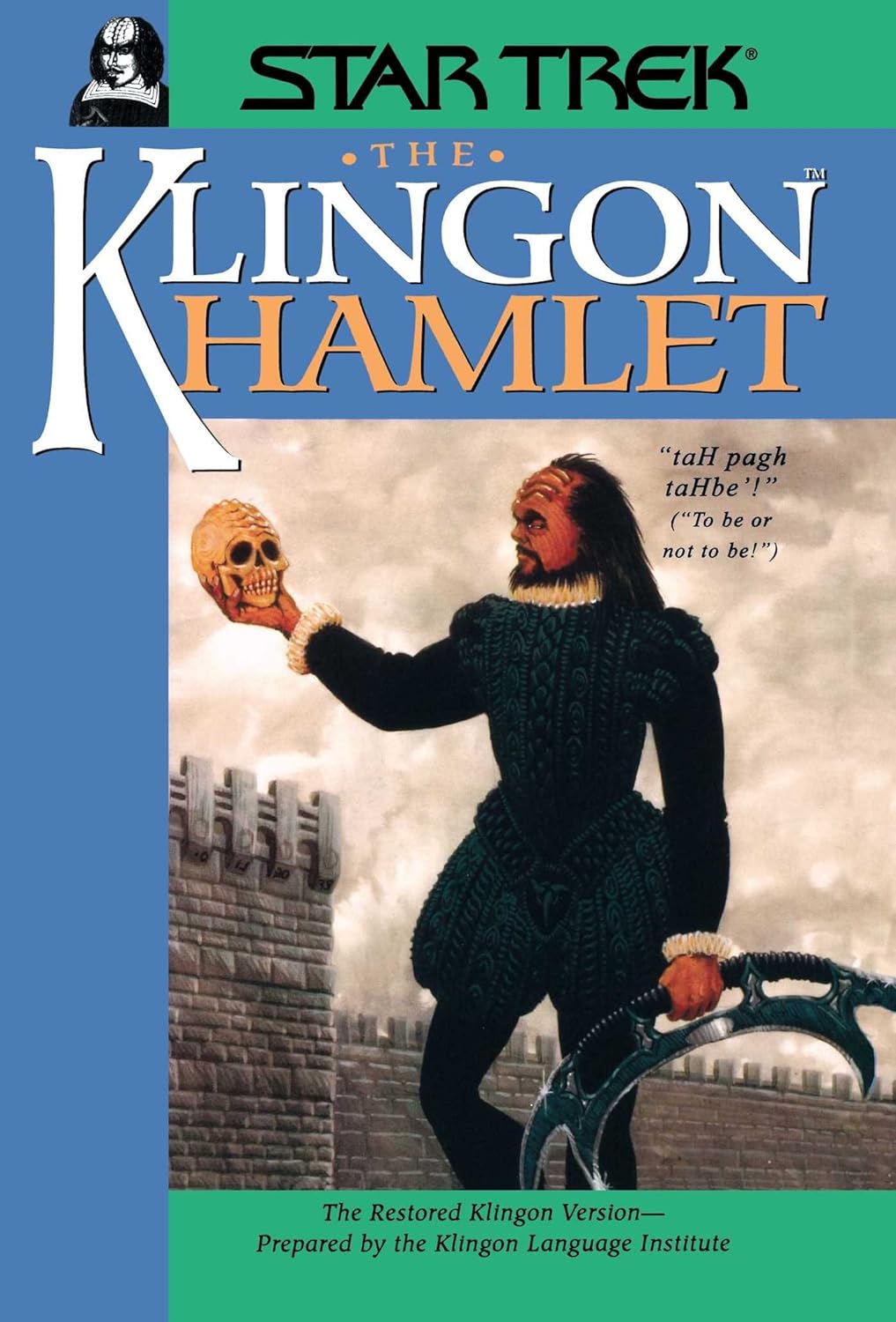

Shakespeare, William. The Klingon Hamlet. Trans. Nick Nicholas, Andrew Strader, and the Klingon Language Institute. New York: Simon & Schuster [Pocket Books], 2000.

Shakespeare, William. The Klingon Hamlet. Trans. Nick Nicholas, Andrew Strader, and the Klingon Language Institute. New York: Simon & Schuster [Pocket Books], 2000..jpg) But I'd like to talk about the book for a minute. In addition to what I'd like to call "The Droes'hQuapleth Engraving" pictured above, the book has some magnificently funny material. As a parody of English Language Studies and Shakespeare studies, the footnotes are priceless.

But I'd like to talk about the book for a minute. In addition to what I'd like to call "The Droes'hQuapleth Engraving" pictured above, the book has some magnificently funny material. As a parody of English Language Studies and Shakespeare studies, the footnotes are priceless.