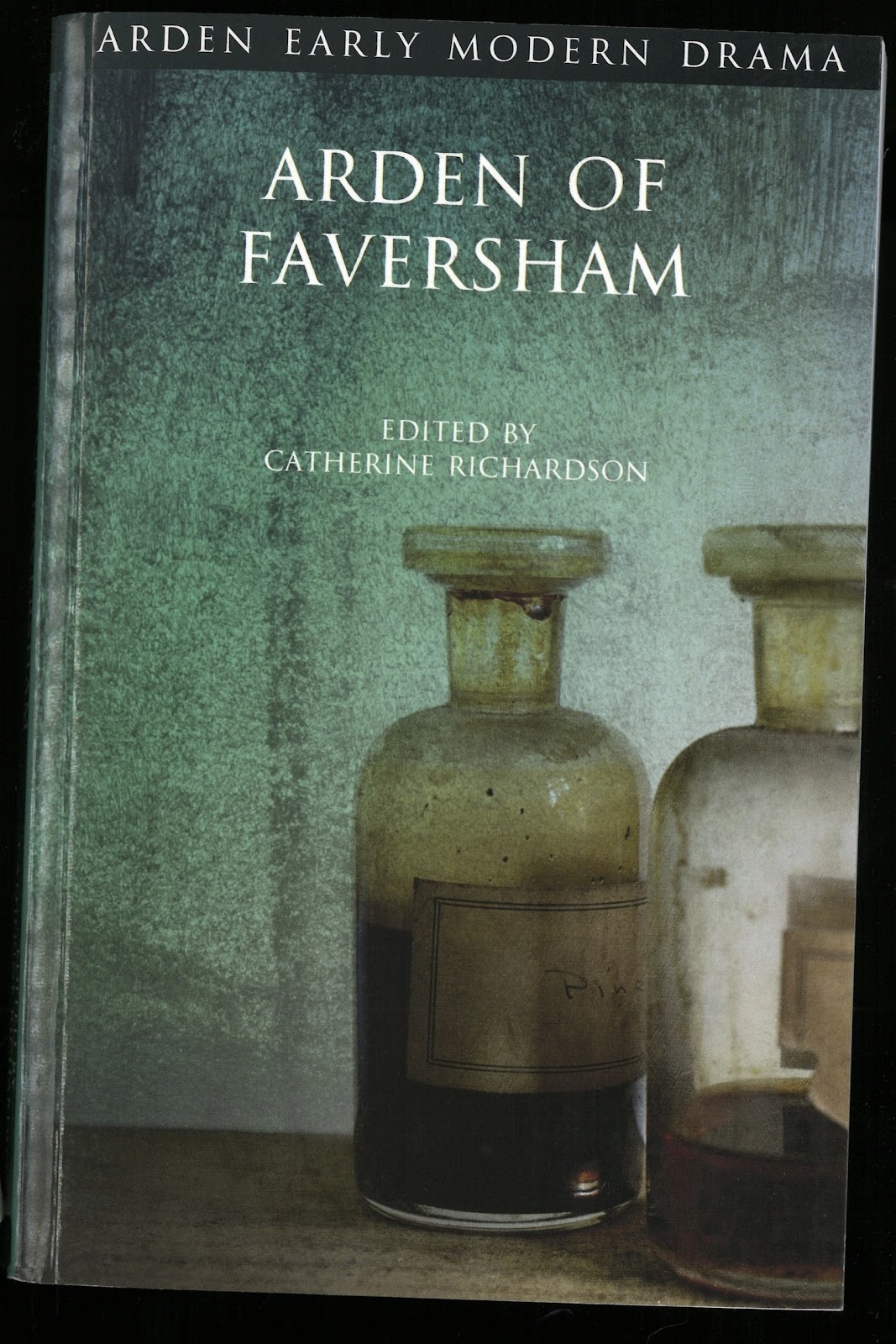

After reading the Arden edition of Arden of Faversham, a play written early in Shakespeare's career with some possible Shakespeare connections (for which, q.v.), I thought it time to give a try to the Arden edition of Double Falsehood, a play that might have some connections to the late part of Shakespeare's career.

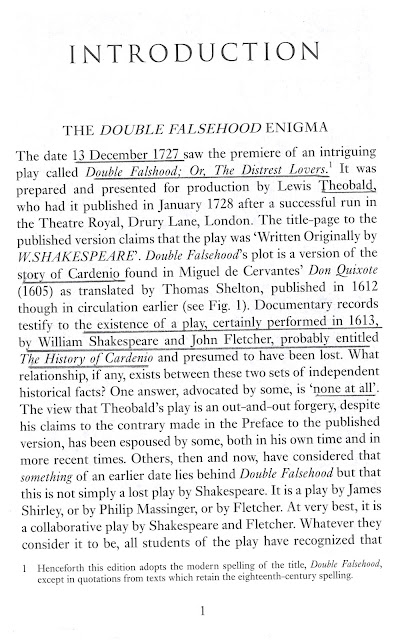

By way of overview, Double Falsehood was a play produced in 1727 by Lewis Theobald, one of the famous earlier editors of Shakespeare. A year later, Theobald printed the play. Theobald said he had three separate manuscripts of a play by Shakespeare on which he based his play. Note that this doesn't mean that any of them were in Shakespeare's hand; "manuscript" just means hand-written rather than printed. The manuscripts are no longer extant.

Three of three steps are available when we think about The Two Noble Kinsmen; only two of three are available in the consideration of Double Falsehood. Yet we can (runs this edition's argument) use the relationship between The Knight's Tale, The Two Noble Kinsmen, and The Rivals to speculate about the relationship between Don Quixote, Cardenio, and Double Falsehood.

I know that my chart has even fewer points of comparison than that proposed by the Arden edition. But the analogy still seems neither relevant nor useful. But it does show the way this edition is grasping at any possible straw to try to find something Shakespearean in Theobald's play. Fortunately, the introduction doesn't spend too much time on that point.

Note, though, the note to I.iii.27.s.d. The twice-repeated "Hmmmmm" there shows my skepticism in an attempt to find something Romeo and Juliet-ey hear.

I would have liked more about that in the introduction—together with some commentary on the shifts from verse to prose and back again. It's rare for a character in Shakespeare to shift in mid-speech. Could this shift (one among many) be indicative of a distinction between Theobald and his source material?

The long and short of my take is that the Arden edition of Double Falsehood is, with some qualifications, a marvelously scholarly edition of a simply dreadful play.

While reading through Brean Hammond's lengthy introduction and apparatus, which runs almost forty pages longer than the text of the play it introduces, I was struck by how nearly every point had a direct or indirect connection to the possibility of Shakespeare's authorship of the play. What echos of Shakespeare can we find in Double Falsehood? Was Theobald a forger or deluded or deceived or genuine? What did Shakespeare know and when did he know it? And so on and on and on.

I know it doesn't sound like me, but I started wanted less about Shakespeare and more about the play itself.

And then I read the play itself—or re-read, really. I had read it once before, many years ago, in a different edition, had not thought much of it, and hadn't done any more with it. On this reading, I realized just how dull and uninspiring it is. The introduction talks about connections to Shakespeare because there's not much to say about the play itself.

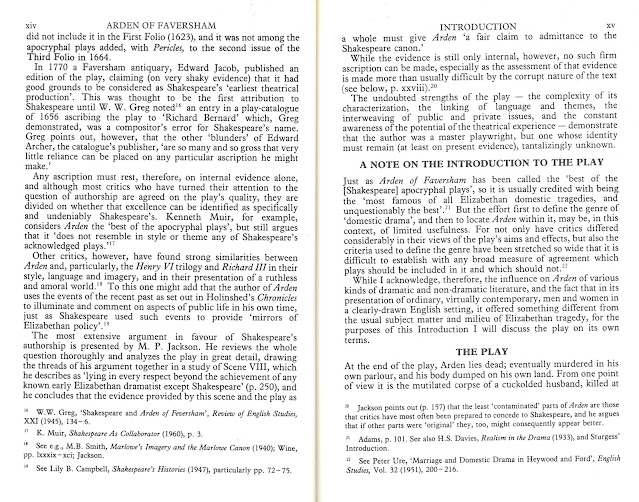

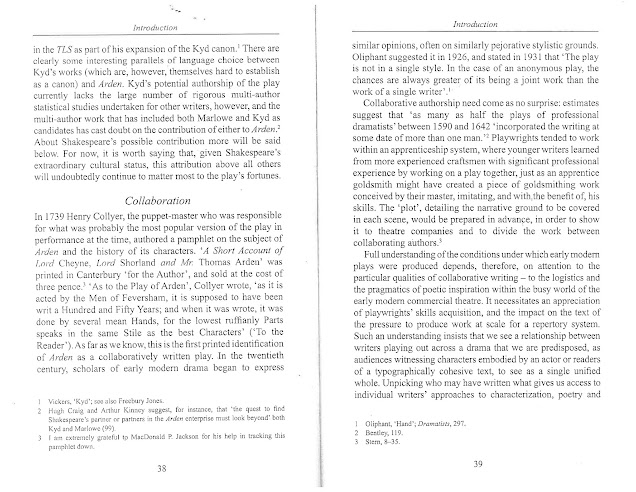

What the edition has to say is mostly scholarly and interesting. By way of example, here are the first few pages. Showing them to you will provide the added benefit of a better and deeper introduction to the play and its questions than I can give.

That should catch us all up pretty well. Serious questions about the three manuscripts call the authenticity of the play we have into question; nonetheless, many scholars think that Theobald's Double Falsehood is a version of an original play written by William Shakespeare in collaboration with John Fletcher.

It's also generally accepted the The Two Noble Kinsmen is a collaborative effort by Shakespeare and Fletcher. That play was itself adapted by William Davenant in 1664 under the title The Rivals. And, as my Grandmother Jones used to day, I told you that to tell you this. That's where this edition makes a strange and irrelevant turn. The argument is that, with The Two Noble Kinsmen, we have the source material (Geoffrey Chaucer's Knight's Tale), the Shakespeare / Fletcher collaboration (The Two Noble Kinsmen), and a restoration adaptation (Davenant's Rivals):

Three of three steps are available when we think about The Two Noble Kinsmen; only two of three are available in the consideration of Double Falsehood. Yet we can (runs this edition's argument) use the relationship between The Knight's Tale, The Two Noble Kinsmen, and The Rivals to speculate about the relationship between Don Quixote, Cardenio, and Double Falsehood.

Not to put too fine a point on it, that seems like nonsense. Imagine that we did not have any of the texts of Hamlet. We know its source, and we know an adaptation of the play. Can we determine anything about the missing play based on those points?

I know that my chart has even fewer points of comparison than that proposed by the Arden edition. But the analogy still seems neither relevant nor useful. But it does show the way this edition is grasping at any possible straw to try to find something Shakespearean in Theobald's play. Fortunately, the introduction doesn't spend too much time on that point.

The play itself doesn't have much to recommend it, but there are still some points of interest. Early in the play, the villainous Henriquez sets out to woo the non-aristocratic Violante. His speeches capture the character of the infatuated quite well:

Note, though, the note to I.iii.27.s.d. The twice-repeated "Hmmmmm" there shows my skepticism in an attempt to find something Romeo and Juliet-ey hear.

When the villainous Henriquez next enters, he's worried that he has raped Violante. Setting aside that there is nothing to prepare the audience for any such action, it's interesting that Henriquez tries to argue that it wasn't rape—even though he admits that "she did not consent" (II.i.37–38) and that "she did resist" (II.i.38):

I would have liked more about that in the introduction—together with some commentary on the shifts from verse to prose and back again. It's rare for a character in Shakespeare to shift in mid-speech. Could this shift (one among many) be indicative of a distinction between Theobald and his source material?

Of equal interest are Violante's speeches after the rape:

Double Falsehood is not a very successful play, but there's a fair amount of interest in its Arden edition.

Click below to purchase the book from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).