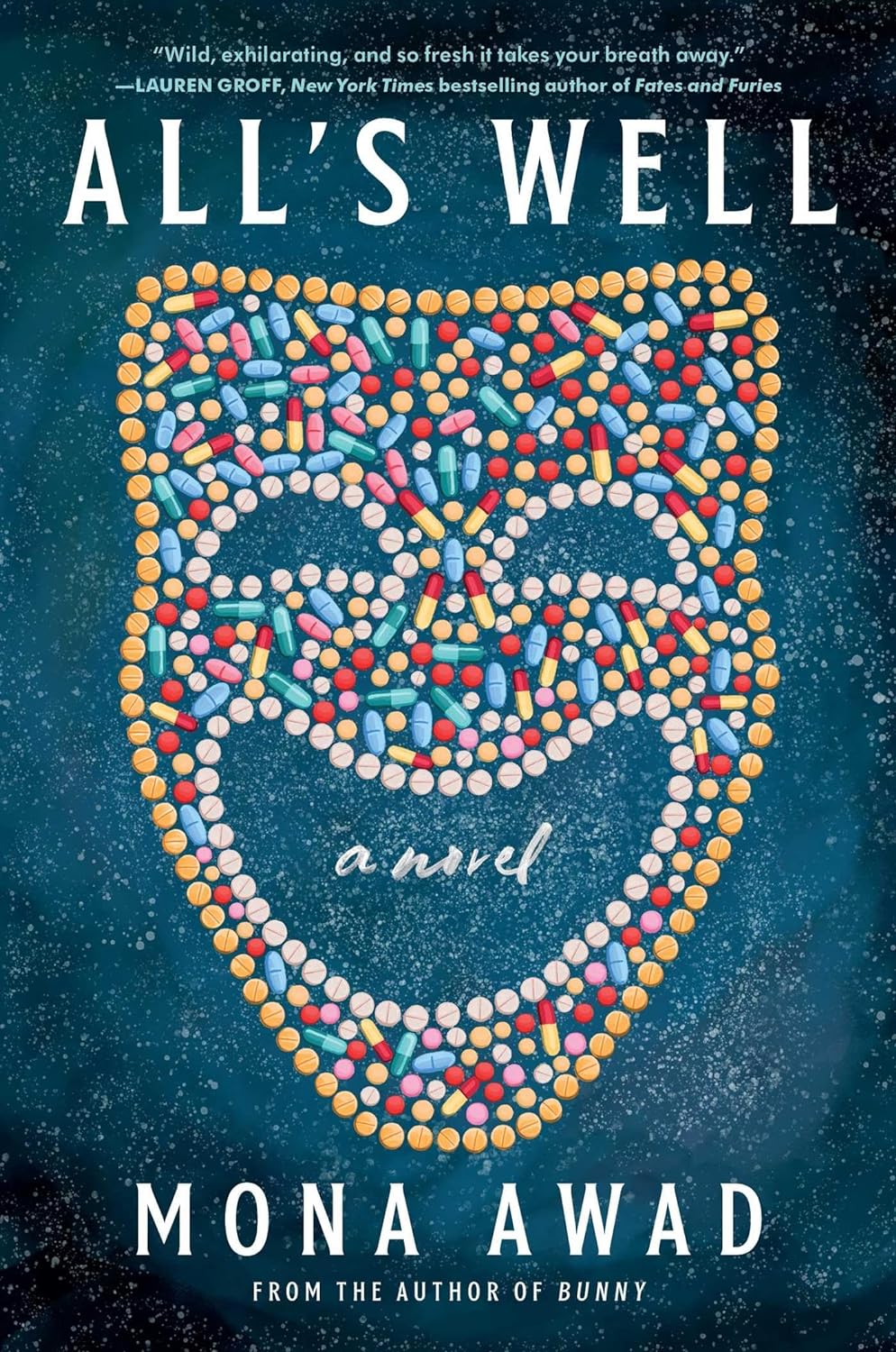

I nearly abandoned this novel several times. It seemed like the first-person narrator was going to talk about two things and two things only: Her chronic pain and her desire to direct a college production of All's Well that Ends Well.

I have some sympathy for (and I considered myself to have some empathy with) the former, and I thought I could be persuaded to have some sympathy with the latter (it's not a play I admire greatly, but if someone is really, genuinely passionate about something—even Wordsworth—I can be swept along with their fascinations).

But it just went on and on. Her chronic pain and reliance on (if not addiction to) a multitude of pain killers was making the work of directing the play difficult. She wasn't able to explain her vision for the play (which seemed to boil down to "Helena was my last successful role, and I loved it, and you're going to love it, too, even if it kills you") to them successfully. And the students (led by the powerful lead actress—powerful not because of her acting but because her parents were huge donors to the school) were mutinying, wanting to put on Macbeth instead. Things were coming to a head about a hundred pages in (it seemed longer) when the administration ordered her to direct Macbeth instead of All's Well.

Therefore, I was going to give up. But I decided to ask, in the words of the immortal Bugs Bunny, "What's the hubbub, bub?"

And I found a number of glowing reviews (e.g., this one from NPR) that said that what I was experiencing was the actual point. The novel is about female chronic pain and the male inability to sympathize with it, empathize with it, or take it seriously.

Well, all right. I don't think I'm guilty of that, but perhaps I am. But perhaps I just don't want to spend a hundred pages being taught that lesson. I remember a line from Gary D. Schmidt's The Wednesday Wars (for which, q.v.) where the main character is complaining about Hamlet. He says, "The ghost was okay, and the gravediggers, but when you write about characters who talk too much, the only way that you can show that they talk too much is to make them talk too much, and that just gets annoying" (235).

So, somewhat guiltily, I gave it another try.

I'm somewhat glad I did—but only somewhat.

The plot from that point on involves Miranda Fitch (our protagonist) meeting with three odd people who seem to have magical powers. They seems to be able to take their pain and send it off to other people. I'm providing that scene as a representative sample of the novel:

It's the turning point of the novel. Miranda Fitch learns this power, gives most of (all of?) her pain to the powerful actress, and, because of a large donation to the college from three strange men who want to see All's Well staged, is able to put on the play she wants rather than Macbeth.

Yes. A lot of irony there.

I won't spoil anything else in the plot, but I found the novel somewhat worth reading—it gets better and more interesting (although also more scattered) after the first hundred pages.

No comments:

Post a Comment