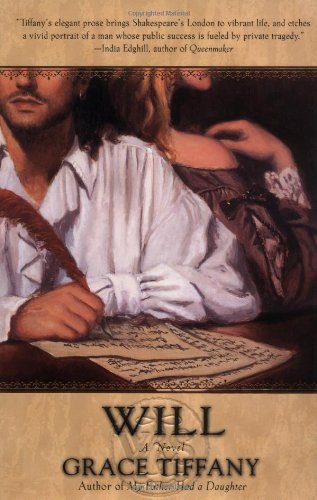

No real surprises await in Grace Tiffany's Will: A Novel, but it's a pleasant read nonetheless. Indeed, without Grace Tiffany's old use of language, the book would fall rather flat.

The novel is a fictional biography of Shakespeare, filling in all the missing pieces—not the least of which is Shakespeare's point of view on things like his wife, his son's death, and his desire to act and write for the London stage. And, since Grace Tiffany is a well-respected Shakespeare scholar in her own right, the novel has (with a few exceptions) a good sense of the contemporary history.

One of the exceptions is having one of Shakespeare's daughters end up disguising herself as a boy and coming to London to try to take her place on the stage. I can't quite place where I've encountered that idea before, but I know another fictional piece or two has toyed with the idea. It's not quite as common as having Elizabeth I attend a performance at the Globe, but it carries the same weight of impossibility—mixed with the interest of the impossible becoming possible.

There's also a wonderfully unlikely scene where Will Shakespeare and Ben Jonson steal a skull from London bridge—the skull of Edward Arden, as it turns out—to play the role of Yorick.

Better than those moments are the points where Shakespeare reflects on his art. In the section below, Shakespeare separates himself and his own views from his characters and their views:

Although we have license to be skeptical of the ways Tiffany fills in the gaps of Shakespeare's biography, this novel is compelling.Mayhap I think the thing the rebel says. Mayhap I do not. He says it, not I. And they hang him. Do I think it right that they hang him? Who may guess? It is not I who speaks, but the play, and the play is poetry, and poetry is many sided. . . . I say only that there is safety in poetry's doubleness. (179-80)

No comments:

Post a Comment