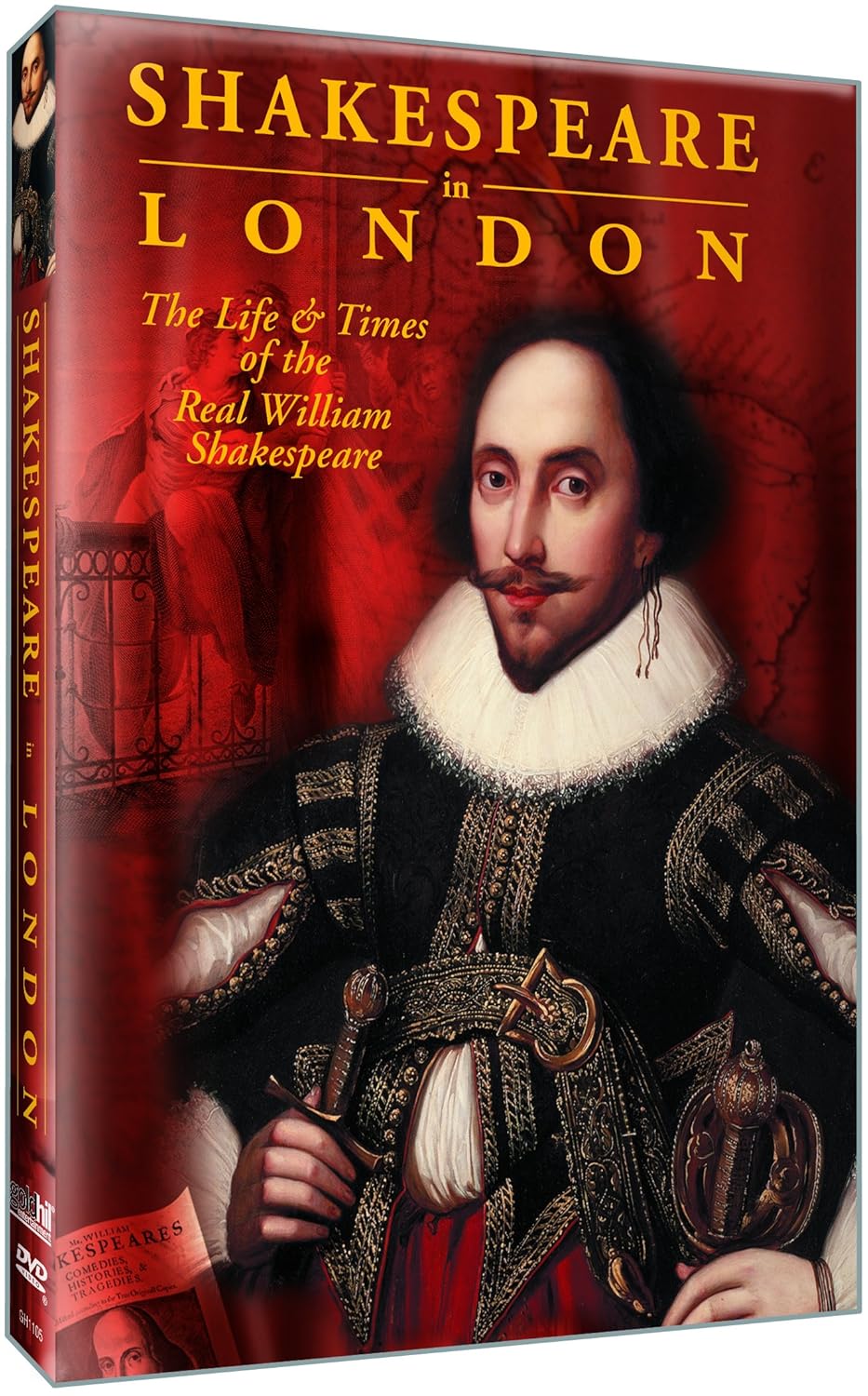

Shakespeare in London: The Life and Times of the Real William Shakespeare. Dir. Mark Ubsdell. Perf. Chrispin Redman, Paul Piper, Keely Beresford. 1999. DVD. Goldhil Entertainment, 2007.

Shakespeare in London: The Life and Times of the Real William Shakespeare. Dir. Mark Ubsdell. Perf. Chrispin Redman, Paul Piper, Keely Beresford. 1999. DVD. Goldhil Entertainment, 2007. Here's a quick personality test for you. Should the title above end with ". . . ve" or ". . . ndon"?

I think the makers of the documentary Shakespeare in London want you to equate the two. They attempt to ride on the coattails of the far more popular and (dare I say it?) vastly superior Shakespeare in Love.

Two instances of this stand out in particular. One is the use of Shakespeare's signatures (see the image above). The opening to Shakespeare in Love shows Shakespeare practicing his own signature. That film may have gotten the idea from the novel No Bed for Bacon (for which, q.v.). Shakespeare in London clearly gets its idea directly from Shakespeare in Love.

The second instance is the decision to use the same speech masterfully delivered by Gwyneth Paltrow in Shakespeare in Love as part of Shakespeare in London's story. The speech is placed right after a ridiculous claim about Queen Elizabeth visiting the theatre in disguise. Perhaps the writers of this documentary took Shakespeare in Love as a documentary itself:

The speech is a magnificent one. For those of you keeping score, it's from Two Gentlemen of Verona, III.i.174-82. It shows what early Shakespeare can do. In Shakespeare in Love, it's compared to Marlowe's heavier lines; here, it seems to serve no purpose—except the purpose of reminding its audience about Shakespeare in Love.

The documentary isn't terrible, but it also doesn't go beyond the basics. When it does, it speculates without indicating that it's being speculative. For example, early in the program, we learn that,

The documentary isn't terrible, but it also doesn't go beyond the basics. When it does, it speculates without indicating that it's being speculative. For example, early in the program, we learn that,The last five words of that are the only non-speculative part. The rest may or may not be true—and it should be presented in that light.For young Shakespeare, life in Stratford has become a life of drugery. He's a poet. He wants to write. Romance beats within his breast. And yet, for him, the marital bed, since the birth of the twins, has become a virtual prison cell. He wonders is this to be his life. And, as far as he can, he wishes to escape. And then, at some time in the mid 1580s, Shakespeare leaves Stratford, abandons his wife, abandons his children, and hits the road for London.

The film is brief (about fifty minutes), the production values are those of a videocassette that has been digitized and burned to DVD, and the acting falters somewhat. But the thing that troubles me most is the attempted reproducton of scenes from Shakespeare in Love. The authors, directors, and actors of that film did it well; why attempt to replicate what they did? I can only think that the producers of Shakespeare in London were waiting to get the rights to incorporate those scenes in their own documentary; when the rights didn't come through, they though, "Oh, well. We can do it ourselves!"

Click below to purchase the film from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

No comments:

Post a Comment