Midleton, Thomas, and William Rowley. The Changeling. Ed. Joost Daalder. A & C Black: London, 1990.

Sidney, Sir Philip. The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia. Ed. Maurice Evans. New York: Penguin, 1977.

The cultural artifact of barley-break doesn't come up very often—particularly as I'm not habitually reading The Two Noble Kinsmen or The Changeling. I'm not even sure if we should say "Let's barley-break" or "Let's play barley-break." But back in my graduate school days, study of things like barley-break, bear baiting, face painting, seeling doves, and processions was all the rage.

I did more work with bear-baiting and seeling doves than with barley-brake, but I did enough to make the diagram above and to work with a section of Sir Philip Sidney's Arcadia (the so-called New Arcadia, a.k.a. The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia) that features the game.

What is barley-break, then (I hear you cry)? You say it's a game, and you invite us to play it . . . but how do we play?

Well, let's start with what the OED says:

Barley-Break, or Last Couple in Hell, is supposed to have acquired the first name because it was played among the barley stacks in the farm-yard. A piece of ground was divided into three parts, the middle portion being called Hell. In this a man and a woman stood, hand in hand, and tried to catch the other players as they advanced, also in couples, from the outer sections. Those who were caught had to take their stand in Hell, and the object of the game was to avoid being the last couple left in that undesirable locality. (36)

I suppose it's something like Red Rover but, when played by adults, having the additional frisson of couples (who may start in love groupings) changing partners.

The longest literary account of a round of the game is Sir Philip Sidney's. The section (from a generic subset of the larger work called the eclogues) is entitled "Lamon's Tale," and you can find the whole thing here. The key element is that the couples who are not in the area called "hell" do not have to hold hands while they try to cross to the other side of the field. On that point, Hole is either mistaken or misleading.

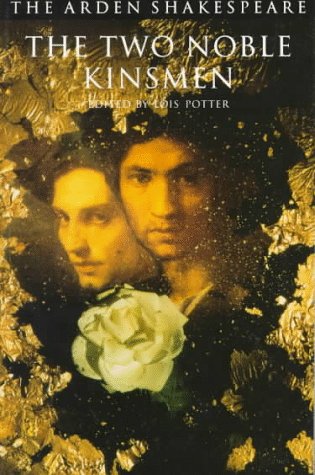

The game makes its way in a minor section of The Two Noble Kinsmen. The jailer's daughter, who has gone insane (cf. Ophelia), rambles on while a doctor listens (cf. Lady Macbeth). Here's part of what she says: "Faith, I'll tell you, sometime we go to barley-break, we of the blessed. Alas, 'tis a sore life they have it's' other place—such burning, frying, boiling, hissing, howling, chattering, cursing: oh, they have shrewd measure; take heed!" (IV.iii.30-34). The image below gives a fuller context (as well as the Arden edition's note on barley-break—which also misleadingly assumes that all the couples had to hold hands during each round of the game):

Finally, barley-break makes its way into The Changeling, a play filled with murder and scheming and adultery. You can read a full synopsis of the play here, but the key elements involved here are the changing of couples and the line from De Flores that connects the game of barley-break with the events of the play: ". . . the while I coupled with your mate / At barley-break. Now we are left in hell" (V.iii.162-63). The image below gives you the context (and the footnotes that the New Mermaids edition provides):

When the weather gets warmer, let's gather to have a round or two of barley-break. After all, it need not actually end in insanity or murder, and it sounds like a fun way to exercise away a spring afternoon.

No comments:

Post a Comment