Sierra, Judy. The Great Dictionary Caper. Illustrated by Eric Comstock. Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, 2018.

As so often happens, I chanced upon these books while searching for something else.

As so often happens, I chanced upon a bit of Shakespeare in each one.

In the business, this is called "SS" or "Serendipitous Shakespeare."

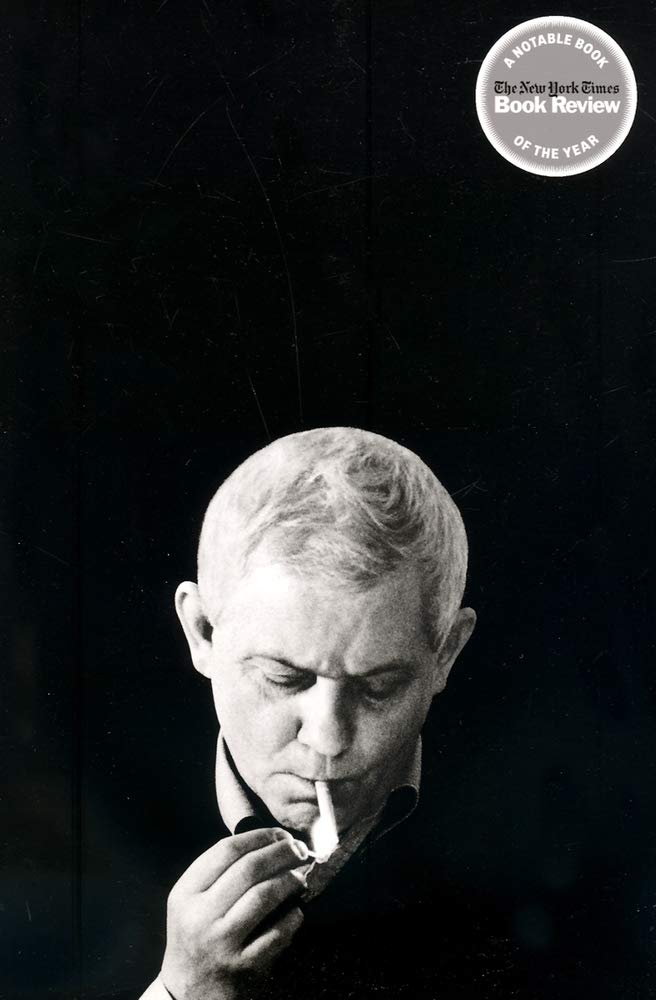

Maurice and his Dictionary, compellingly written and marvelously illustrated, tells the story of a family's flight from the holocaust from the point of view of one of the sons. They leave Belgium in 1940 and travel to the north of France, the south of France, and Spain before ending up in Jamacia. Maurice, wanting to learn English, spends some of the little money he has to buy Cambers's Twentieth Century Dictionary. Eventually, he attends university in Canada.

The image below shows Maurice preforming Shakespeare while attending Jamaica College, a well-respected high school in Kingston.

The Great Dictionary Caper has a loose narrative about words escaping from Noah Webster's dictionary. That's far less important than the collection of words in various categories covered by the book. Shakespearean words get a page of their own:

The Great Dictionary Caper has a loose narrative about words escaping from Noah Webster's dictionary. That's far less important than the collection of words in various categories covered by the book. Shakespearean words get a page of their own:

Of course, entire children's books have been written about Shakespeare's words—see Flibbertigibbety Words: Young Shakespeare Chases Inspiration or Will's Words: How William Shakespeare Changed the Way You Talk (for which, q.v.)—but a two-page spread was just right for this book.

Either book would make a great addition to your children's book library. Don't hesitate; give them a try!

Click below to purchase the books from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).