Maguire, Laurie, and Emma Smith. 30 Great Myths about Shakespeare. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013.

This is really quite a delightful book. Its authors treat a wide range of myths about Shakespeare—some of which are less mythy and more debatable than others (i.e., "Shakespeare was a Catholic")—in a perfect marriage of popular expression and scholarship.

The book addresses the myths thoroughly, exploring how and why the myths came to be and providing good documentation to support its claims.

Myth number 30 addresses the authorship issue. Even though the authors, in debunking that myth, perpetuate the separate but related myth that Orson Welles was an Oxfordian (he wasn't), I can forgive them because the rest of the chapter is compelling and well-written.

To intrigue you all the more, I'm provided an image of the table of contents—for the first fifteen myths. Enjoy!

Thursday, January 31, 2013

Wednesday, January 30, 2013

Shakespeare . . . Lost . . . in . . . Space!

"The Space Creature." By Irwin Allen and William Welch. Perf. Guy Williams, June Lockhart, and Mark Goddard. Dir. Sobey Martin. Lost in Space. Season 3, episode 10. CBS. 15 November 1967. DVD. Twentieth-Century Fox, 2008.

This was the first—and it may be the last—episode of Lost in Space that I've ever watched. My attention was called to it by the same reader who had found allusions to Shakespeare in Buffy, the Vampire Slayer.

In this episode, upon the disappearance of Dr. Smith, Robot (who has his own Shakespearean connection, being designed by the designer of Robbie, the Robot, of the Tempest-related Forbidden Planet) holds the ice bag Dr. Smith had on his head earlier and gives us part of Hamlet's Yorick speech:

Links: The Episode at IMDB.

This was the first—and it may be the last—episode of Lost in Space that I've ever watched. My attention was called to it by the same reader who had found allusions to Shakespeare in Buffy, the Vampire Slayer.

In this episode, upon the disappearance of Dr. Smith, Robot (who has his own Shakespearean connection, being designed by the designer of Robbie, the Robot, of the Tempest-related Forbidden Planet) holds the ice bag Dr. Smith had on his head earlier and gives us part of Hamlet's Yorick speech:

I don't have much to say beyond that—except to note that this is one more instance of the pervasiveness of Shakespeare in modern Western culture.

Links: The Episode at IMDB.

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

Othello and Buffy, the Vampire Slayer

“Earshot.” By Joss Whedon and Jane Espenson. Dir. Regis Kimble. Perf. Sarah Michelle Gellar, Nicholas Brendon, and Emma Caulfield. Buffy, the Vampire Slayer. Season 3, episode 18. The WB Television Network. 28 September 1999. DVD. 20th Century Fox, 2010.

The same reader who pointed me toward the possibility of a Titus Andronicus reference in Buffy, the Vampire Slayer (for which, q.v.) gave me a tip about the show's use of Othello.

This one was much easier to find—though you can see by the subtitles that I chose to watch this at three times the speed (which is a reflection on my limited time rather than on the show's value). Buffy has developed the ability to hear what other people are thinking, and she uses it to (1) act like she knows the right answers in class and (2) reach an epiphany about her own jealousy. I'll let the clip speak the rest for itself:

Links: The Episode at IMDB.

The same reader who pointed me toward the possibility of a Titus Andronicus reference in Buffy, the Vampire Slayer (for which, q.v.) gave me a tip about the show's use of Othello.

This one was much easier to find—though you can see by the subtitles that I chose to watch this at three times the speed (which is a reflection on my limited time rather than on the show's value). Buffy has developed the ability to hear what other people are thinking, and she uses it to (1) act like she knows the right answers in class and (2) reach an epiphany about her own jealousy. I'll let the clip speak the rest for itself:

Links: The Episode at IMDB.

Monday, January 28, 2013

Another Shakespearean FoxTrot

Amend, Bill. Wrapped-up FoxTrot: A Treasury with the Final Daily Strips. Kansas City: Andrews McMeel, 2009. 103.

Give me a B!

B!

Give me an I!

I!

Give me an L!

L!

Give me another L!

L!

Give me an Amend!

Amend!

Thanks. That's filled up the space enough that this comic by Bill Amend will fit.

Click on the image below to enlarge it. Enjoy!

Give me a B!

B!

Give me an I!

I!

Give me an L!

L!

Give me another L!

L!

Give me an Amend!

Amend!

Thanks. That's filled up the space enough that this comic by Bill Amend will fit.

Click on the image below to enlarge it. Enjoy!

Friday, January 25, 2013

The Renaissance Feud in The Facts of Life

"E.G.O.C. (Edna Garrett on Campus)." By Janis Hirsch. Perf. Charlotte Rae, Lisa Whelchel, Kim Fields, Mindy Cohn, Nancy McKeon, and Clive Revill. Dir. John Bowab. The Facts of Life. Season 6, episode 8. NBC. 14 November 1984.

I'm trying to be much better about passing along the bits and bobs (and books and blocks) of Shakespeare that I find as I encounter them instead of several months or years after. That will mean that some posts will be much more informative than analytical, but I hope none of you will be offended by that. After all, this is a MicroBlog!

Today, I'm pointing you toward an episode of The Facts of Life I learned about from Shakespeare Geek's Twitter Feed. The housemother of a woman's boarding school returns to college to pursue an English major. She ends up in a Shakespeare class, and the professor decides to play a game he calls "The Renaissance Feud."

Links: The Episode at IMDB.

I'm trying to be much better about passing along the bits and bobs (and books and blocks) of Shakespeare that I find as I encounter them instead of several months or years after. That will mean that some posts will be much more informative than analytical, but I hope none of you will be offended by that. After all, this is a MicroBlog!

Today, I'm pointing you toward an episode of The Facts of Life I learned about from Shakespeare Geek's Twitter Feed. The housemother of a woman's boarding school returns to college to pursue an English major. She ends up in a Shakespeare class, and the professor decides to play a game he calls "The Renaissance Feud."

The premise is all right, but I'm not convinced that its working out is the best it could be. Still—there it is!

Links: The Episode at IMDB.

Click below to purchase the complete series from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

Thursday, January 24, 2013

Shakespeare in The Twilight Zone: “Fear”

“Fear.” By Rod Serling. Perf. Peter Mark Richman and Hazel Court. Dir. Ted Post. The Twilight Zone. Season 5, episode 35. CBS. 29 May 1964. DVD. Image Entertainment, 2005.

The Shakespeare in this episode is bound to be a bit anti-climactic, especially after "The Bard." And it also is the second time the show has turned to this quote. The clip pretty much speaks for itself, needing no further plot summary. And the quote—well, the quote speaks directly to the philosophy of The Twilight Zone: "There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy."

Links: The Episode at Wikipedia.

The Shakespeare in this episode is bound to be a bit anti-climactic, especially after "The Bard." And it also is the second time the show has turned to this quote. The clip pretty much speaks for itself, needing no further plot summary. And the quote—well, the quote speaks directly to the philosophy of The Twilight Zone: "There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy."

Links: The Episode at Wikipedia.

Click below to purchase the complete season from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

Wednesday, January 23, 2013

Shakespeare in The Twilight Zone: “Queen of the Nile”

"Queen of the Nile." By Jerry Sohl. Perf. Ann Blyth, Lee Philips, Celia Lovsky, and Frank Ferguson. Dir. John Brahm. The Twilight Zone. Season 5, episode 23. CBS. 6 March 1964. DVD. Image Entertainment, 2005.

Here's another tiny Shakespearean element (or are there two?) in an episode of The Twilight Zone.

A journalist arrives at an actress's mansion to interview her—with special attention to her youth and vitality. When he skeptically asks her about one of her early films (Queen of the Nile, 1940, co-starring Charles Danforth), made when she was only fifteen, she replies, "Darling, Juliet was only twelve."

Links: The Episode at Wikipedia.

Here's another tiny Shakespearean element (or are there two?) in an episode of The Twilight Zone.

A journalist arrives at an actress's mansion to interview her—with special attention to her youth and vitality. When he skeptically asks her about one of her early films (Queen of the Nile, 1940, co-starring Charles Danforth), made when she was only fifteen, she replies, "Darling, Juliet was only twelve."

The second possible (and merely tangential) connection to Shakespeare involves a spoiler. If you don't mind discovering a secret of the episode, scroll down a little further and read on.

It's possible that the actress is Cleopatra—the very Cleopatra of Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra herself—also known for her youth and vitality. That point is open to debate, but it is within the realm of possibility.

Links: The Episode at Wikipedia.

Click below to purchase the complete season from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

Shakespeare in The Twilight Zone: “The Bard”

“The Bard.” By Rod Serling. Perf. Jack Weston, John Williams, Henry Lascoe, Marge Redmond, and Burt Reynolds. Dir. David Butler. The Twilight Zone. Season 4, episode 18. CBS. 23 May 1963. DVD. Image Entertainment, 2004.

“The Bard.” By Rod Serling. Perf. Jack Weston, John Williams, Henry Lascoe, Marge Redmond, and Burt Reynolds. Dir. David Butler. The Twilight Zone. Season 4, episode 18. CBS. 23 May 1963. DVD. Image Entertainment, 2004.Note: This is a repost of a 2010 blog post entitled "Extending Shakespeare's Biography: Shakespeare in The Twilight Zone" (for which, q.v.).

Speculations about what Shakespeare would be doing if he were alive today are not uncommon. Would he be Twittering? Would he be composing Broadway musicals? Would he make it to Hollywood? Would he make it in Hollywood once he made to Hollywood?

In one such extended speculation, The Twilight Zone offers a Shakespeare brought back from the great beyond to help a failing tele-script writer. And Shakespeare doesn't look too happy to be in 1963 or to be in The Twilight Zone.

It's a outstandingly funny episode, and it's all the more remarkable for its characterization of Rocky Rhodes, the most devoted disciple of Stanislavsky that ever lived—played by a very young Burt Reynolds! He'll make an appearance in the clip below, criticizing Shakespeare for not liking Tennessee Williams.

The overall plot centers on Julius Moomer, a television scriptwriter who uses black magic to bring Shakespeare to Hollywood. He hopes Shakespeare will help him make it big.

And Shakespeare does help—but the studio executives can't quite figure out what to do with his scripts. And the sponsors keep objecting to certain lines and wanting to change things. In what appears to be a Romeo and Juliet-inspired script, for example, they alter the balcony scene. The male lead meets the female lead in a subway station rather than on a balcony. Later, a horrified Shakespeare learns that his ending has been changed. Esmeralda (the Juliet analogue) doesn’t kill herself. She runs away with a bass fiddler from Artie Shaw’s Gramercy Five.

And Shakespeare does help—but the studio executives can't quite figure out what to do with his scripts. And the sponsors keep objecting to certain lines and wanting to change things. In what appears to be a Romeo and Juliet-inspired script, for example, they alter the balcony scene. The male lead meets the female lead in a subway station rather than on a balcony. Later, a horrified Shakespeare learns that his ending has been changed. Esmeralda (the Juliet analogue) doesn’t kill herself. She runs away with a bass fiddler from Artie Shaw’s Gramercy Five.As a result, the script seems to be a hodge-podge of Shakespeare and modern (modern to the 1960s, that is) lingo:

The best parts are when Shakespeare works his own lines into the conversation—often citing their source. Here's the knock-down-drag-out fight that ends Shakespeare's career in television:Actor One: “Oh, come, Olivia. Cast off those benighted colors and . . . and gaze as a friend on Greenwich Village. Let not forever with your veiled eyes seek your noble boyfriend in the dust. It is common, I know. But all that live must die.”

Actor Two: “Oh, it’s easy for you to say.”

Shakespeare, in that moment, seems to prove himself the master of both the language of his day and the language of ours, even as he disparages the modern television industry with lines spoken by Falstaff in The Merry Wives of Windsor:Shakespeare: “‘Blow, blow, thou winter wind, thou art not so unkind as man’s ingratitude.’ That’s from As You Like It, Act II, scene vii.”

Moomer: “Hey, Will! Will! Hey! Wait a minute, Will! Wait a minute. What are you doing? You're going to louse up the whole deal. What am I going to say to them in there? What am I going to tell them?”

Shakespeare: “Tell them simply that ‘Foolerly, sir, does walk about the orb like the sun; it shines everywhere.’ Act III, scene i, Twelfth Night. And you, Julius Moomer, foolish mortal who could have covered himself with a cloak of immortality, to you, Julius Moomer, who has succumbed to the rankest compound of villainous smell that ever offended nostril—to you, Julius Moomer . . . Lottsa Luck.”

All in all, the episode provides a humorous and fascinating use of Shakespeare and his biography—extended, in this case, to 1963.By the Lord, a buck-basket! Rammed me in with foul shirts and smocks, socks, foul stockings, greasy napkins; that, Master Brook, there was the rankest compound of villanous smell that ever offended nostril. (III.v.89-93)

Links: The Episode at IMDB.

Click below to purchase the complete season from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

Tuesday, January 22, 2013

Shakespeare in The Twilight Zone: “The Incredible World of Horace Ford”

“The Incredible World of Horace Ford.” By Reginald Rose. Perf. Pat Hingle, Nan Martin, Ruth White, Phillip Pine, Vaughn Taylor, Jerry Davis, and Jim E. Titus. Dir. Abner Biberman. The Twilight Zone. Season 4, episode 15. CBS. 18 April 1963. DVD. Image Entertainment, 2005.

Although it has only a small amount of Shakespeare, “The Incredible World of Horace Ford” has a great deal of interest.

Horace, the protagonist of this episode, is turning forty, and he is reflecting back with considerable nostalgia on his childhood in the 1930s on Randolph Street in New York City. He recalls all the kids he used to play with and all the games they used to play. And then he finds himself going back in time to Randolph Street, where he sees his former playmates, who are still around ten years old. Two points of interest arise out of this.

The first is one of the games the kids are playing. In the sequences set in the 1930s, we hear one of the children call "Ringolevio, caw, caw, caw!" I knew nothing about the game before watching this episode, but it is a well-documented game played (under that name) specifically in New York City. It sounds similar to the game called "Capture the Flag" that I played growing up. You can read a lengthy entry about it on Wikipedia. Or you can read a book titled Ringolevio: A Life Played for Keeps.

The second is a set of words associated with a set of actions that Horace says one kid of his acquaintance was known for. The kid would make a fist, say, "Shake" while shaking it, "Spear" while poking another kid in the side with it, and "Sock an ear" while bumping the kid on the ear. Together, it comes out quickly as "Shakespeare—sock an ear!" Horace demonstrates the actions in the clip below (and there's a bit more afterwards that has the cry of "Ringolevio"):

Links: The Episode at Wikipedia.

Bonus Material: The Lyrics to Allan Sherman's "Turn Back the Clock":

Turn back the clock and recall what you did

Back on the block where you lived as a kid.

And if you think every kid nowadays

Is a nut or a kook or a fool,

Just turn back the clock and recall what you said

When you were a kid in school.

Ah, your mother wears army shoes!

Nyah nyah nyah nyah nyah nyah.

Teacher, teacher, I declare,

I see your purple underwear.

Margarite, go wash your feet,

The board of health's across the street.

Ladies and gentlemen, take my advice,

Pull down your pants and slide on the ice.

Inka binka, bottle of ink,

The cork fell out and you stink.

Nyah nyah nyah nyah nyah nyah.

Mary had a little lamb,

The doctor was surprised!

Mary had a little lamb,

She also had a bear.

I've often seen her little lamb,

But I've never seen her bare.

Nyah nyah nyah nyah nyah nyah.

Roses are red, violets are blue,

I copied your paper and I flunked too.

Roses are red, violets are blue,

Whenever it rains, I think of you—drip, drip, drip!

Roses are red, violets are blue,

I still say your mother wears army shoes!

Nyah nyah nyah nyah nyah nyah.

Your mother is a burglar,

Your father is a spy,

And you're the dirty little rat

Who told the F.B.I.

Dirty Lil, Dirty Lil,

Lives on top of Garbage Hill,

Never took a bath and never will,

Yuck, pooey, Dirty Lil.

Oh what a face, oh what a figure,

Two more legs and you'd look like Trigger!

A B C D goldfish?

L M N O goldfish.

S A R 2 goldfish. C M?

Turn back the clock and recall what you did

Back on the block where you lived as a kid.

And if you think every kid nowadays

Is a nut or a kook or a fool,

Just turn back the clock and recall what you said

When you were a kid in school.

There goes your father wearing your mother's army shoes!

Although it has only a small amount of Shakespeare, “The Incredible World of Horace Ford” has a great deal of interest.

Horace, the protagonist of this episode, is turning forty, and he is reflecting back with considerable nostalgia on his childhood in the 1930s on Randolph Street in New York City. He recalls all the kids he used to play with and all the games they used to play. And then he finds himself going back in time to Randolph Street, where he sees his former playmates, who are still around ten years old. Two points of interest arise out of this.

The first is one of the games the kids are playing. In the sequences set in the 1930s, we hear one of the children call "Ringolevio, caw, caw, caw!" I knew nothing about the game before watching this episode, but it is a well-documented game played (under that name) specifically in New York City. It sounds similar to the game called "Capture the Flag" that I played growing up. You can read a lengthy entry about it on Wikipedia. Or you can read a book titled Ringolevio: A Life Played for Keeps.

The second is a set of words associated with a set of actions that Horace says one kid of his acquaintance was known for. The kid would make a fist, say, "Shake" while shaking it, "Spear" while poking another kid in the side with it, and "Sock an ear" while bumping the kid on the ear. Together, it comes out quickly as "Shakespeare—sock an ear!" Horace demonstrates the actions in the clip below (and there's a bit more afterwards that has the cry of "Ringolevio"):

I had also never heard of "Shakespeare—sock an ear." And that's true even after a childhood filled with the songs of Allan Sherman. His "Turn Back the Clock" features tons of rhymes and sayings that kids of Sherman's generation used to say. And now I want to know how widespread or well-known "Shakespeare—sock an ear" was. I currently have a call into the amazing and knowledgeable people of the public radio show A Way With Words, and I hope they'll have some news for me.

In the meantime, enjoy this clip—and please comment below if you know anything about "Shakespeare—sock an ear."

Links: The Episode at Wikipedia.

Click below to purchase the complete season from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

Bonus Material: The Lyrics to Allan Sherman's "Turn Back the Clock":

Turn back the clock and recall what you did

Back on the block where you lived as a kid.

And if you think every kid nowadays

Is a nut or a kook or a fool,

Just turn back the clock and recall what you said

When you were a kid in school.

Ah, your mother wears army shoes!

Nyah nyah nyah nyah nyah nyah.

Teacher, teacher, I declare,

I see your purple underwear.

Margarite, go wash your feet,

The board of health's across the street.

Ladies and gentlemen, take my advice,

Pull down your pants and slide on the ice.

Inka binka, bottle of ink,

The cork fell out and you stink.

Nyah nyah nyah nyah nyah nyah.

Mary had a little lamb,

The doctor was surprised!

Mary had a little lamb,

She also had a bear.

I've often seen her little lamb,

But I've never seen her bare.

Nyah nyah nyah nyah nyah nyah.

Roses are red, violets are blue,

I copied your paper and I flunked too.

Roses are red, violets are blue,

Whenever it rains, I think of you—drip, drip, drip!

Roses are red, violets are blue,

I still say your mother wears army shoes!

Nyah nyah nyah nyah nyah nyah.

Your mother is a burglar,

Your father is a spy,

And you're the dirty little rat

Who told the F.B.I.

Dirty Lil, Dirty Lil,

Lives on top of Garbage Hill,

Never took a bath and never will,

Yuck, pooey, Dirty Lil.

Oh what a face, oh what a figure,

Two more legs and you'd look like Trigger!

A B C D goldfish?

L M N O goldfish.

S A R 2 goldfish. C M?

Turn back the clock and recall what you did

Back on the block where you lived as a kid.

And if you think every kid nowadays

Is a nut or a kook or a fool,

Just turn back the clock and recall what you said

When you were a kid in school.

There goes your father wearing your mother's army shoes!

Monday, January 21, 2013

Shakespeare in The Twilight Zone: “Printer's Devil”

“Printer's Devil.” By Charles Beaumont. Perf. Burgess Meredith, Robert Sterling, Pat Crowley, and Ray Teal. Dir. Ralph Senensky. The Twilight Zone. Season 4, episode 9. CBS. 28 February 1963. DVD. Image Entertainment, 2005.

“Printer's Devil.” By Charles Beaumont. Perf. Burgess Meredith, Robert Sterling, Pat Crowley, and Ray Teal. Dir. Ralph Senensky. The Twilight Zone. Season 4, episode 9. CBS. 28 February 1963. DVD. Image Entertainment, 2005.Although it's not much, it is Shakespeare.

In this episode, the character of Mr. Smith is played by Burgess Meredith, whom we last saw hoping to spend the rest of his days reading Shakespeare and other great authors (for which, q.v.). Mr. Smith is the devil; when his advances toward the Editor-in-Chief's friend are spurned, he dismisses her with a curt title of a Shakespeare play: Love's Labour [sic] Lost:

Links: The Episode at Wikipedia.

Click below to purchase the complete season from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

Shakespeare in The Twilight Zone: “Little Girl Lost”

“Little Girl Lost.” By Richard Matheson. Perf. Robert Sampson, Sarah Marshall, Tracy Stratford, Rhoda Williams, and Charles Aidman. Dir. Paul Stewart. The Twilight Zone. Season 3, episode 26. CBS. 16 March 1962. DVD. Image Entertainment, 2005.

At the end of this episode's opening sequence, there's a tiny, tiny bit of Shakespeare.

Somehow, Rod Serling can't resist saying “There’s the rub” (and citing his source) as he tells us what's peculiar about what's happening in the lives of this family:

Links: The Episode at Wikipedia.

At the end of this episode's opening sequence, there's a tiny, tiny bit of Shakespeare.

Somehow, Rod Serling can't resist saying “There’s the rub” (and citing his source) as he tells us what's peculiar about what's happening in the lives of this family:

Links: The Episode at Wikipedia.

Click below to purchase the complete season from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

Friday, January 18, 2013

Shakespeare in The Twilight Zone: “A Quality of Mercy”

“A Quality of Mercy.” By Rod Serling. Perf. Dean Stockwell, Albert Salmi, Leonard Nimoy, Rayford Barnes, Ralph Votrian, Dale Ishimoto, Jerry Fujikawa, and Michael Pataki. Dir. Buzz Kulik. The Twilight Zone. Season 3, episode 15. CBS. 29 December 1961. DVD. Image Entertainment, 2005.

This episode's title—and the Shakespeare quotation at its close—come from Portia's speech to Shylock in Act IV:

Links: The Episode at Wikipedia.

This episode's title—and the Shakespeare quotation at its close—come from Portia's speech to Shylock in Act IV:

The episode's plot is a fairly-straightforward "put yourself in the other guy's shoes" narrative. An American soldier has been ordered to attack a group of Japanese soldiers in a cave; he inexplicably finds himself to be a Japanese solider preparing a similar attack on American soldiers in a cave. Through this, he learns, in essence, the Golden Rule.The quality of mercy is not strain'd,

It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven

Upon the place beneath . . . .

It blesseth him that gives and him that takes. (IV.i.184-87)

At the episode's close, Rod Serling points toward the universality of the sentiment expressed by Portia: it is "applicable to any moment in time, to any group of soldiery, to any nation on the face of the earth—or, as in this case, to the Twilight Zone."

Links: The Episode at Wikipedia.

Click below to purchase the complete season from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

Thursday, January 17, 2013

Shakespeare in The Twilight Zone: “The Passersby”

“The Passersby.” By Rod Serling. Perf. James Gregory, Joanne Linville, Warren Kemmerling, and Austin Green. Dir. Elliot Silverstein. The Twilight Zone. Season 3, episode 4. CBS. 6 October 1961. DVD. Image Entertainment, 2005.

I haven't yet seen the new movie Lincoln, but, true to Lincoln's character, the film contains (as I gather) a fair bit of Shakespeare.

I told you that to tell you this: When Abe Lincoln shows up in The Twilight Zone, it's with Shakespeare on his lips.

This episode, which is on the dramatic side, features a road—a road that the dead of the Civil War walk as they leave this earth. I hope I'm not giving away a spoiler by saying that Lincoln has to walk this road as well.

As he does so, a line from Julius Caesar seems fitting to him:

Links: The Episode at Wikipedia.

I haven't yet seen the new movie Lincoln, but, true to Lincoln's character, the film contains (as I gather) a fair bit of Shakespeare.

I told you that to tell you this: When Abe Lincoln shows up in The Twilight Zone, it's with Shakespeare on his lips.

This episode, which is on the dramatic side, features a road—a road that the dead of the Civil War walk as they leave this earth. I hope I'm not giving away a spoiler by saying that Lincoln has to walk this road as well.

As he does so, a line from Julius Caesar seems fitting to him:

Perhaps because they're too familiar, Lincoln leaves out the first two lines of Caesar's words—the more famous part of the speech:Of all the wonders that I yet have heard,

It seems to me most strange that men should fear,

Seeing that death, a necessary end,

Will come when it will come. (II.ii.34-37)

The result is that the speech seems more sensitive—less prone to accusations of bragging—and that, too, seems in keeping with Lincoln's character.Cowards die many times before their deaths,

The valiant never taste of death but once. (II.ii.32-33)

Links: The Episode at Wikipedia.

Click below to purchase the complete season from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

Wednesday, January 16, 2013

Shakespeare in The Twilight Zone: “The Purple Testament”

“The Purple Testament.” By Rod Serling. Perf. William Reynolds, Dick York, Barney Phillips, and Warren Oates. Dir. Richard L. Bare. The Twilight Zone. Season 1, episode 19. CBS. 12 February 1960. DVD. Image Entertainment, 2004.

In this episode, a soldier has the ability to see who is going to die that day. The gift terrifies him, and he starts to exhibit signs of a nervous breakdown.

At the end of the episode (which you should see for yourself—I'll try to avoid spoilers), Rod Serling's voice comes in and gives a quote from Richard II (which he mistakenly attributes to Richard III): “. . . he is come to open / The purple testament of bleeding war” (Richard II, III.iii.93-94).

Links: The Episode at Wikipedia.

In this episode, a soldier has the ability to see who is going to die that day. The gift terrifies him, and he starts to exhibit signs of a nervous breakdown.

At the end of the episode (which you should see for yourself—I'll try to avoid spoilers), Rod Serling's voice comes in and gives a quote from Richard II (which he mistakenly attributes to Richard III): “. . . he is come to open / The purple testament of bleeding war” (Richard II, III.iii.93-94).

Links: The Episode at Wikipedia.

Click below to purchase the complete season from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

Tuesday, January 15, 2013

Shakespeare in The Twilight Zone: “The Last Flight”

“The Last Flight.” By Richard Matheson. Perf. Kenneth Haigh, Simon Scott, Alexander Scourby, and Robert Warwick. Dir. William Claxton. The Twilight Zone. Season 1, episode 18. CBS. 5 February 1960. DVD. Image Entertainment, 2004.

The Shakespeare in this episode is carefully and thoughtfully integrated into the show's ending. The plot involves a pilot from World War I fleeing from a battle, leaving one of his comrades alone and in danger, by flying into a mysterious cloud. He lands in the 1950s, recognizes his cowardice, and flies back into a similar mysterious cloud to finish the battle.

In the clip below, the officers from the 1950s meet up with the pilot's comrade—who bore the nickname "Old Leadbottom" (but only among the few members of his squadron)—and say, in a very Shakespearean way, that they will recount to him the details of what's happened off stage.

At that point, the camera turns to the window to show us a mysterious cloud. The voice of Rod Serling closes the episode with the quotation that follows the clip—a quote that is very apropos of The Twilight Zone in general.

Dialogue from a play: Hamlet to Horatio: "There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy." Dialogue from a play written long before men took to the sky. There are more things in heaven and earth and in the sky than perhaps can be dreamt of. And somewhere in between heaven, the sky, the earth lies the Twilight Zone.

Links: The Episode at Wikipedia.

The Shakespeare in this episode is carefully and thoughtfully integrated into the show's ending. The plot involves a pilot from World War I fleeing from a battle, leaving one of his comrades alone and in danger, by flying into a mysterious cloud. He lands in the 1950s, recognizes his cowardice, and flies back into a similar mysterious cloud to finish the battle.

In the clip below, the officers from the 1950s meet up with the pilot's comrade—who bore the nickname "Old Leadbottom" (but only among the few members of his squadron)—and say, in a very Shakespearean way, that they will recount to him the details of what's happened off stage.

At that point, the camera turns to the window to show us a mysterious cloud. The voice of Rod Serling closes the episode with the quotation that follows the clip—a quote that is very apropos of The Twilight Zone in general.

Dialogue from a play: Hamlet to Horatio: "There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy." Dialogue from a play written long before men took to the sky. There are more things in heaven and earth and in the sky than perhaps can be dreamt of. And somewhere in between heaven, the sky, the earth lies the Twilight Zone.

Links: The Episode at Wikipedia.

Click below to purchase the complete season from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

Monday, January 14, 2013

Welcome to Shakespeare in The Twilight Zone Week at Bardfilm

“Time Enough at Last.” By Rod Serling. Perf. Burgess Meredith. Dir. John Brahm. The Twilight Zone. Season 1, episode 8. CBS. 20 November 1959. DVD. Image Entertainment, 2004.

A while ago, I watched and listened to all the episodes of The Twilight Zone that I could get my hands on. In the course of doing so, I amassed a fair number of Shakespeare references in the shows.

Starting today, I'll be posting on those references, allusions, or quotations. I'll try to stick to references within the shows themselves—if an episode has a Shakespearean title but no Shakespearean content (as is the case with "Perchance to Dream," episode nine of season one), I won't even mention it.

Here, then, is the first mention of Shakespeare in The Twilight Zone—and it's one of the show's most famous episodes. A man who loves nothing better than to read—but who is prevented from doing so by the daily calls on his time by other concerns—finds himself the only survivor of a nuclear attack. In the clip below, he realizes that he will now be able to read without interruption:

Links: The Episode at Wikipedia.

A while ago, I watched and listened to all the episodes of The Twilight Zone that I could get my hands on. In the course of doing so, I amassed a fair number of Shakespeare references in the shows.

Starting today, I'll be posting on those references, allusions, or quotations. I'll try to stick to references within the shows themselves—if an episode has a Shakespearean title but no Shakespearean content (as is the case with "Perchance to Dream," episode nine of season one), I won't even mention it.

Here, then, is the first mention of Shakespeare in The Twilight Zone—and it's one of the show's most famous episodes. A man who loves nothing better than to read—but who is prevented from doing so by the daily calls on his time by other concerns—finds himself the only survivor of a nuclear attack. In the clip below, he realizes that he will now be able to read without interruption:

Shakespeare appears in a delightfully-alliterative trio of great authors: "Shelley, Shakespeare, Shaw."

Links: The Episode at Wikipedia.

Click below to purchase the complete season from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

Friday, January 11, 2013

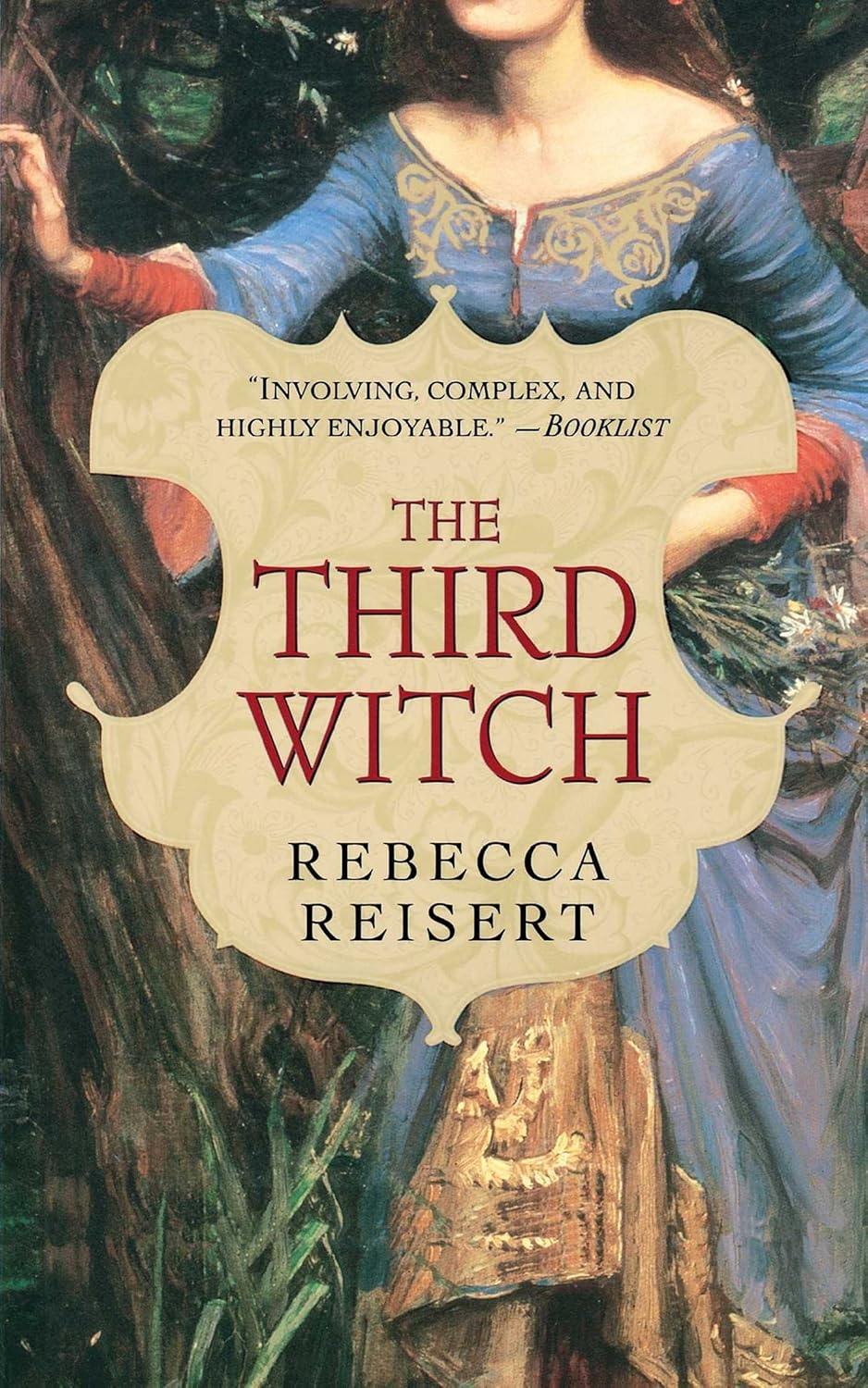

Book Note: The Third Witch

Reisert, Rebecca. The Third Witch. New York: Washington Square Press, 2002.

This novel is not just another retelling of Macbeth. The development of character, of setting, and of plot are all superior, as is the writing itself.

In The Third Witch, elements of the plot of Macbeth are carefully and skillfully interwoven with an immense, overarching narrative of the life of Gillyflower, the youngest of the three Wëird Sisters. For reasons that do not become clear until the end of the novel (and I'll offer no spoilers on that subject here), Gillyflower has vowed to obtain revenge on Macbeth—almost always called "Him" with a capital H by our narrator.

Nettle and Mad Helga are the other two witches, and they reluctantly—and with the same kind of equivocal warnings they offer Macbeth—aid her in her revenge. Gilly's impatience at the process is one of the most delightful and humorous points of this novel. They meet Macbeth and Banquo and enact a scene pretty much like the one in Act I, scene iii of the play. Immediately after, Gilly basically says, "That's it? That's revenge? What an anti-climax!" and goes off to try to push her revenge along a bit.

As a sample, I'm providing pages ten to twelve in the images below (click on them to enlarge them). They will give you a good sense of the quality of the novel as a whole and of the narrator's character at this point in the novel.

This novel is not just another retelling of Macbeth. The development of character, of setting, and of plot are all superior, as is the writing itself.

In The Third Witch, elements of the plot of Macbeth are carefully and skillfully interwoven with an immense, overarching narrative of the life of Gillyflower, the youngest of the three Wëird Sisters. For reasons that do not become clear until the end of the novel (and I'll offer no spoilers on that subject here), Gillyflower has vowed to obtain revenge on Macbeth—almost always called "Him" with a capital H by our narrator.

Nettle and Mad Helga are the other two witches, and they reluctantly—and with the same kind of equivocal warnings they offer Macbeth—aid her in her revenge. Gilly's impatience at the process is one of the most delightful and humorous points of this novel. They meet Macbeth and Banquo and enact a scene pretty much like the one in Act I, scene iii of the play. Immediately after, Gilly basically says, "That's it? That's revenge? What an anti-climax!" and goes off to try to push her revenge along a bit.

As a sample, I'm providing pages ten to twelve in the images below (click on them to enlarge them). They will give you a good sense of the quality of the novel as a whole and of the narrator's character at this point in the novel.

The novel is quite impressive—it's a well-written, innovative parallel narrative to Macbeth—and I highly recommend it.

Thursday, January 10, 2013

Book Note: Cymbeline in The Boggart

Cooper, Susan. The Boggart. Logan: Perfection Learning, 2004.

When I was quite young, I fell in love with Susan Cooper's books. I read Over Sea, Under Stone and the rest of the books in The Dark is Rising series with wonder and awe. And I still can't get enough of her Shakespeare-related young adult novel King of Shadows (for which, q.v.).

I was much older when The Boggart came out, but one passage in particular has stuck with me for over twenty years.

The plot of the young adult novel involves (this may be self-evident) a boggart—a mischievous sprite—facing the death of the last direct descendant of the Scottish clan he has haunted for centuries upon centuries and the subsequent grief that overwhelms him. The only other time he felt such grief was a thousand years ago when another chieftain of the clan died.

The only relatives of the MacDevon family are both quite distant and Canadian. The Boggart is locked in a desk that is then transported to Canada, and he must face this brave new world that has such technology in it.

I'm providing you with a long segment of the novel. In it, the Boggart has travelled with the children of the family to the theatre in which their father works. The company is rehearsing a production of Cymbeline, and the Boggart simultaneously explores the theatre's lighting panel and feels, through the words of the play, the grief of his double loss of MacDevon chieftains—one ancient and one modern. The scene never fails to move me deeply.

Here, then, are pages 111 to 119 of Susan Cooper's The Boggart.

The Boggart watched all this in speechless delight. From the moment he entered the auditorium, he had been enchanted. This building held a small world in which he felt instantly totally at home; a world of magic, where the rules of ordinary human life seemed not to apply. A wooden floor could become a living forest; an actor with pins stuck all around his tunic could become a wild young man threatening murder; night could become day. The Boggart was particularly entranced by the lighting changes. That was more than he could manage in his world. How did they do it? He flittered down over the seats to Robert’s table, inquisitive.

Robert was studying the stage. “Too warm, don’t you think?” he said to one of the men with earphones.

“Let’s pull down the amber on the cyc,” said the man into his microphone. “Give me twenty percent, okay?”

The Boggart did not find this helpful. He flittered on around the theater, up onto the stage, where he looked up and saw the battery of light instruments hanging from the roof grid, blazing at him; out again into the darkness of the auditorium. At the back of the house he saw a square of light and flittered over to investigate that. Behind the window he saw the stage manager sitting at the light board, wearing earphones, her fingers playing with a keyboard as the Boggart had seen Jessup play with his computer. The computer had never seemed of much interest to the Boggart, but this keyboard, it appeared, was the source of every change in that magical array of lights over the stage. Fascinated, the Boggart began looking for a way into the little room.

Under the light board, docile old Fred the theater dog lifted his head from the stage manager’s feet, his ears suddenly erect. He jumped to his feet, nearly knocking the stage manager out of her chair, and began barking hysterically.

“Shut up, Fred!” said the stage manager irritably.

Fred barked louder. He bared his teeth, snarling between barks, straining to see out of the window into the theater. The stage manager whacked at him ineffectually, trying to hear the instructions squawking into her headset. Fred swung around and began barking at the door, leaping up at it, whining, frantic.

“Get out, then, you idiot!” yelled the stage manager, and she pulled the door open. Fred tumbled out in a clamor of barks and yelps—and just before the door closed, the Boggart flittered calmly in.

Fred sniffed the air, snarled and reversed himself, attacking the door again in a noisy frenzy. A passing stagehand seized him by the collar and dragged him away.

The play went on. Onstage, out of the entrance to the cave came Willie, booming away in his leathery costume, with Meg dressed as a young man, and two real young men dressed in the same curious fashion as Willie. Emily and Jessup sat watching in the back row. The two young men seemed to be brothers, and to think that Meg was also their brother. They were going hunting, but when they weren’t looking Meg secretly and mysteriously swallowed some kind of drug, and retreated into the cave to sleep. Then Cloten came on with his sword, and was left alone with one of the young men, Polydore, whom he rudely called a “villain mountaineer.” They began to fight.

Jessup loved the fight, and tried nor to bounce in his seat. Cloten had a sword and Polydore had only a dagger, but was clearly going to win. It was at the end of the fight, as they clashed their way off the stage, that the lights in the theater began to go mad.

The changes were gradual, but extraordinary. At first, the brightness of the lighting remained the same, but it took on a faint reddish tinge, growing stronger in color until it was a deep scarlet. From the cries of consternation in Robert’s group, Emily realized this was not a light cue planned by the director or his designer. She crept out of her seat and down the aisle until she was in earshot, and heard her father uttering a number of four-letter words he did not normally use in her presence. In the darkness, she grinned to herself.

The lighting began to change color again, and she realized that it was going very slowly through the spectrum: red, orange, yellow. . . . Jessup slipped into a seat beside her. On the stage, the actors, occasionally looking nervously up at the light grid, went on speaking their lines, probably because Robert was too busy cursing to tell them to stop. As the lights began to turn from yellow to green, Polydore came back onstage proudly holding Cloten’s chopped-off head aloft. Emily heard Jessup cheer.

The lights began to darken to blue. The lighting designer was shouting into his microphone. Up in the light booth the stage manager was waving her arms about. Onstage, just as the lights changed from blue to indigo and began to merge into purple, Willie came deliberately down to the front of the stage and recited his next lines straight at Robert.

He boomed:

Emily said softly, “No—the Boggart.”

“Oh my gosh!” said Jessup in horror.

Ahead of them Robert called back grimly, “Just keep going, Willie.”

“Never trust a computer,” said Willie. He went back to his Shakespeare voice. “They are as gentle . . . ”

Jessup craned his head to look back at the window behind which the stage manager and an electrician were both now flapping their arms. He hissed at Emily, “You really think he’s in there operating the board, invisible?”

Emily said, “Don’t you?”

But then the lights made a different kind of change. The purple glow which dominated the stage faded swiftly away into a clear light like early morning, fresh and cool. It seemed to ripple gently, as if wisps of cloud were floating over an unseen sun.

“Now that’s more like it!” said Robert in relief. “What gobo is that, Phil?”

“I’m not sure,” said the designer. He peered at the stage nervously.

“It’s beautiful!” Robert said. He settled back happily into his seat, and on the stage the actors’ voices began to lose the tension that had made them all, even Willie, sound much higher-pitched than normal. Polydore came back onstage and announced that he had sent Cloten’s chopped-off head floating down the stream, and as Willie laughed the light seemed to laugh with him, taking on a wonderful brilliant gaiety. Then unexpectedly the theater filled with deep, slow, solemn music, and the actors expressed surprise and the light seemed to glimmer with it too.

“Lovely!” said Robert, enchanted. “I don’t know what you’re doing, but it’s perfect!”

The lighting designer made a small strangled noise of baffled gratitude, and whispered frantically into his microphone.

On the stage, Polydore’s brother entered, carrying Meg in his arms. He didn’t know she was only asleep after taking the mysterious drug—he thought she was dead, and so did Polydore and Willie. Watching the way Meg let her body droop into emptiness, so did Emily. “O melancholy!” cried Willie, and the light filling the stage became muted and strange, like an embodiment of grief.

“Oh yes!” cried Robert in delight. He clapped Phil the lighting designer on the back.

“What is that?” hissed Phil into his microphone to the stage manager at the light board.

But the stage manager didn’t know. Watching, admiring but desperare, she knew she would never be able to reproduce the wonderful effects the computer was instructing the lights to shine at the stage—because she was not controlling the computer. It was taking no notice of any instructions she punched into its keyboard. It was designing the lighting pattern itself.

And inside the computer, the Boggart was beside himself with delight. He had taken the lights through the spectrum of all the colors as an exercise, a way of teaching himself how to use them. Now he knew the language of light and he was speaking it. By his own magic, he was using the magic of this new technological world in which he found himself—and the mixing of the two magics was a wonder. In the theater, Emily and Jessup and all the company members watched it without daring to breathe, knowing they had never seen anything like this on a stage before. Lyrical and mysterious, the lights shifted and flickered and glowed, like echoes of the words the bemused actors were saying on the stage.

They lasted until the song. It was a song of mourning over the supposed dead body of Meg / Imogen, and its words were not actually sung, but spoken, because the character Polydore in the play claimed that he would weep if he tried to sing. (“Shakespeare wrote it that way because he had an actor with a lousy singing voice,” Robert told them pithily, much later.) But the words themselves, having been written by the man who was the greatest master of the English language who will ever live, held an enchantment that cut right through the Boggart’s magic to the Boggart himself. They reached his heart, and found in it the old deep sorrow of his double loss: the deaths of the only two human beings he had loved, Duncan and Devon MacDevon.

The whole place was possessed by his sorrowing. Like a dark cloud it swallowed the consciousness of everyone listening. Emily felt a misery blacker than anything she had ever felt before; Jessup felt himself a desolate deserted baby, wanting to howl for his mother; Robert was back in the bleakest moment of his own much longer life, the moment he tried always unsuccessfully to forget, and so was every grown man or woman there.

The voices of the two actors went on, clear, intertwining.

The sound grew and grew, louder and louder, closer and closer, intolerably close and loud, filling the theater so that all the listeners inside it longed to flatten their hands against their ears to shut out the terrible wave of grief.

Then at the peak of the noise it was gone, vanished, and the light died with it, leaving the theater silent and dark.

When I was quite young, I fell in love with Susan Cooper's books. I read Over Sea, Under Stone and the rest of the books in The Dark is Rising series with wonder and awe. And I still can't get enough of her Shakespeare-related young adult novel King of Shadows (for which, q.v.).

The plot of the young adult novel involves (this may be self-evident) a boggart—a mischievous sprite—facing the death of the last direct descendant of the Scottish clan he has haunted for centuries upon centuries and the subsequent grief that overwhelms him. The only other time he felt such grief was a thousand years ago when another chieftain of the clan died.

The only relatives of the MacDevon family are both quite distant and Canadian. The Boggart is locked in a desk that is then transported to Canada, and he must face this brave new world that has such technology in it.

I'm providing you with a long segment of the novel. In it, the Boggart has travelled with the children of the family to the theatre in which their father works. The company is rehearsing a production of Cymbeline, and the Boggart simultaneously explores the theatre's lighting panel and feels, through the words of the play, the grief of his double loss of MacDevon chieftains—one ancient and one modern. The scene never fails to move me deeply.

Here, then, are pages 111 to 119 of Susan Cooper's The Boggart.

The Boggart watched all this in speechless delight. From the moment he entered the auditorium, he had been enchanted. This building held a small world in which he felt instantly totally at home; a world of magic, where the rules of ordinary human life seemed not to apply. A wooden floor could become a living forest; an actor with pins stuck all around his tunic could become a wild young man threatening murder; night could become day. The Boggart was particularly entranced by the lighting changes. That was more than he could manage in his world. How did they do it? He flittered down over the seats to Robert’s table, inquisitive.

Robert was studying the stage. “Too warm, don’t you think?” he said to one of the men with earphones.

“Let’s pull down the amber on the cyc,” said the man into his microphone. “Give me twenty percent, okay?”

The Boggart did not find this helpful. He flittered on around the theater, up onto the stage, where he looked up and saw the battery of light instruments hanging from the roof grid, blazing at him; out again into the darkness of the auditorium. At the back of the house he saw a square of light and flittered over to investigate that. Behind the window he saw the stage manager sitting at the light board, wearing earphones, her fingers playing with a keyboard as the Boggart had seen Jessup play with his computer. The computer had never seemed of much interest to the Boggart, but this keyboard, it appeared, was the source of every change in that magical array of lights over the stage. Fascinated, the Boggart began looking for a way into the little room.

Under the light board, docile old Fred the theater dog lifted his head from the stage manager’s feet, his ears suddenly erect. He jumped to his feet, nearly knocking the stage manager out of her chair, and began barking hysterically.

“Shut up, Fred!” said the stage manager irritably.

Fred barked louder. He bared his teeth, snarling between barks, straining to see out of the window into the theater. The stage manager whacked at him ineffectually, trying to hear the instructions squawking into her headset. Fred swung around and began barking at the door, leaping up at it, whining, frantic.

“Get out, then, you idiot!” yelled the stage manager, and she pulled the door open. Fred tumbled out in a clamor of barks and yelps—and just before the door closed, the Boggart flittered calmly in.

Fred sniffed the air, snarled and reversed himself, attacking the door again in a noisy frenzy. A passing stagehand seized him by the collar and dragged him away.

The play went on. Onstage, out of the entrance to the cave came Willie, booming away in his leathery costume, with Meg dressed as a young man, and two real young men dressed in the same curious fashion as Willie. Emily and Jessup sat watching in the back row. The two young men seemed to be brothers, and to think that Meg was also their brother. They were going hunting, but when they weren’t looking Meg secretly and mysteriously swallowed some kind of drug, and retreated into the cave to sleep. Then Cloten came on with his sword, and was left alone with one of the young men, Polydore, whom he rudely called a “villain mountaineer.” They began to fight.

Jessup loved the fight, and tried nor to bounce in his seat. Cloten had a sword and Polydore had only a dagger, but was clearly going to win. It was at the end of the fight, as they clashed their way off the stage, that the lights in the theater began to go mad.

The changes were gradual, but extraordinary. At first, the brightness of the lighting remained the same, but it took on a faint reddish tinge, growing stronger in color until it was a deep scarlet. From the cries of consternation in Robert’s group, Emily realized this was not a light cue planned by the director or his designer. She crept out of her seat and down the aisle until she was in earshot, and heard her father uttering a number of four-letter words he did not normally use in her presence. In the darkness, she grinned to herself.

The lighting began to change color again, and she realized that it was going very slowly through the spectrum: red, orange, yellow. . . . Jessup slipped into a seat beside her. On the stage, the actors, occasionally looking nervously up at the light grid, went on speaking their lines, probably because Robert was too busy cursing to tell them to stop. As the lights began to turn from yellow to green, Polydore came back onstage proudly holding Cloten’s chopped-off head aloft. Emily heard Jessup cheer.

The lights began to darken to blue. The lighting designer was shouting into his microphone. Up in the light booth the stage manager was waving her arms about. Onstage, just as the lights changed from blue to indigo and began to merge into purple, Willie came deliberately down to the front of the stage and recited his next lines straight at Robert.

He boomed:

Willie paused. “Vi-o-let!” he said pointedly. “Who’s running the light board—Shakespeare?”“O thou goddess,

Thou divine nature, thou thyself thou blazon’st

In these two princely boys! They are as gentle

As zephyrs blowing below the violet—”

Emily said softly, “No—the Boggart.”

“Oh my gosh!” said Jessup in horror.

Ahead of them Robert called back grimly, “Just keep going, Willie.”

“Never trust a computer,” said Willie. He went back to his Shakespeare voice. “They are as gentle . . . ”

Jessup craned his head to look back at the window behind which the stage manager and an electrician were both now flapping their arms. He hissed at Emily, “You really think he’s in there operating the board, invisible?”

Emily said, “Don’t you?”

But then the lights made a different kind of change. The purple glow which dominated the stage faded swiftly away into a clear light like early morning, fresh and cool. It seemed to ripple gently, as if wisps of cloud were floating over an unseen sun.

“Now that’s more like it!” said Robert in relief. “What gobo is that, Phil?”

“I’m not sure,” said the designer. He peered at the stage nervously.

“It’s beautiful!” Robert said. He settled back happily into his seat, and on the stage the actors’ voices began to lose the tension that had made them all, even Willie, sound much higher-pitched than normal. Polydore came back onstage and announced that he had sent Cloten’s chopped-off head floating down the stream, and as Willie laughed the light seemed to laugh with him, taking on a wonderful brilliant gaiety. Then unexpectedly the theater filled with deep, slow, solemn music, and the actors expressed surprise and the light seemed to glimmer with it too.

“Lovely!” said Robert, enchanted. “I don’t know what you’re doing, but it’s perfect!”

The lighting designer made a small strangled noise of baffled gratitude, and whispered frantically into his microphone.

On the stage, Polydore’s brother entered, carrying Meg in his arms. He didn’t know she was only asleep after taking the mysterious drug—he thought she was dead, and so did Polydore and Willie. Watching the way Meg let her body droop into emptiness, so did Emily. “O melancholy!” cried Willie, and the light filling the stage became muted and strange, like an embodiment of grief.

“Oh yes!” cried Robert in delight. He clapped Phil the lighting designer on the back.

“What is that?” hissed Phil into his microphone to the stage manager at the light board.

But the stage manager didn’t know. Watching, admiring but desperare, she knew she would never be able to reproduce the wonderful effects the computer was instructing the lights to shine at the stage—because she was not controlling the computer. It was taking no notice of any instructions she punched into its keyboard. It was designing the lighting pattern itself.

And inside the computer, the Boggart was beside himself with delight. He had taken the lights through the spectrum of all the colors as an exercise, a way of teaching himself how to use them. Now he knew the language of light and he was speaking it. By his own magic, he was using the magic of this new technological world in which he found himself—and the mixing of the two magics was a wonder. In the theater, Emily and Jessup and all the company members watched it without daring to breathe, knowing they had never seen anything like this on a stage before. Lyrical and mysterious, the lights shifted and flickered and glowed, like echoes of the words the bemused actors were saying on the stage.

They lasted until the song. It was a song of mourning over the supposed dead body of Meg / Imogen, and its words were not actually sung, but spoken, because the character Polydore in the play claimed that he would weep if he tried to sing. (“Shakespeare wrote it that way because he had an actor with a lousy singing voice,” Robert told them pithily, much later.) But the words themselves, having been written by the man who was the greatest master of the English language who will ever live, held an enchantment that cut right through the Boggart’s magic to the Boggart himself. They reached his heart, and found in it the old deep sorrow of his double loss: the deaths of the only two human beings he had loved, Duncan and Devon MacDevon.

The words overwhelmed the Boggart, filling him with a terrible grief at the loss not only of Duncan and the MacDevon, but of his own home. He came blundering out of the computer that governed the theater lights, and flittered back unthinking into the auditorium. He was filled with love and grief and longing, and the force of his feeling took hold of everyone inside the theater, on the stage or behind it or in front of it.“Fear no more the heat o’ the sun,

Nor the furious winter’s rages;

Thou thy worldly task hast done,

Home art gone, and ta’en thy wages:

Golden lads and girls all must,

As chimney-sweepers, come to dust. ”

The whole place was possessed by his sorrowing. Like a dark cloud it swallowed the consciousness of everyone listening. Emily felt a misery blacker than anything she had ever felt before; Jessup felt himself a desolate deserted baby, wanting to howl for his mother; Robert was back in the bleakest moment of his own much longer life, the moment he tried always unsuccessfully to forget, and so was every grown man or woman there.

The voices of the two actors went on, clear, intertwining.

The voices fell silent. And in the dim light that was left, gradually the theater began to fill with an eerie sound which belonged not to the play but to the Boggart, to the pain of life and loss that he was feeling. Soft, faraway, coming closer, there was the throb of a muffled drumbeat, ta-rum . . . ta-rum . . . ta-rum . . . and over it the plaintive music of a lament played on a single bagpipe; and over that too, like an echo, the curious husky sound of the shuffling of many feet.“No exorciser harm thee!

Nor no witchcraft charm thee!

Ghost unlaid forbear thee!

Nothing ill come near thee!

Quiet consummation have;

And renowned be thy grave!”

The sound grew and grew, louder and louder, closer and closer, intolerably close and loud, filling the theater so that all the listeners inside it longed to flatten their hands against their ears to shut out the terrible wave of grief.

Then at the peak of the noise it was gone, vanished, and the light died with it, leaving the theater silent and dark.

Wednesday, January 9, 2013

Book Note: The Heat of the Sun

Rain, David. The Heat of the Sun: A Novel. New York: Henry Holt, 2012.

The title of this novel comes from Cymbeline. Imogen, Cymbeline's daughter, has disguised herself as a man named Fidele and travelled to Wales. There she meets Guiderius and Arviragus, Cymbeline's sons, who are disguised as the shepherds Polydore and Cadwal. Imogen has swallowed a Julietesque sleeping draft, and the brothers think her dead. They sing a beautiful song of mourning over her:

Early in the novel, Trouble arrives at our narrator's boarding school. At first, he is wildly popular; he then sinks into the utmost disrepute. In the scene that has the most Shakespeare, Trouble (in disrepute) is one of the boys who are reading out loud from Cymbeline in their English class. Here's the scene (click on the image below to enlarge it and to make it legible):

The title of this novel comes from Cymbeline. Imogen, Cymbeline's daughter, has disguised herself as a man named Fidele and travelled to Wales. There she meets Guiderius and Arviragus, Cymbeline's sons, who are disguised as the shepherds Polydore and Cadwal. Imogen has swallowed a Julietesque sleeping draft, and the brothers think her dead. They sing a beautiful song of mourning over her:

The Heat of the Sun does not do very much with the plot of Cymbeline, though it is quite a compelling novel all the same. The plot involves political intrigue and scandal from the early 1900s to the use of the atomic bomb in World War Two (and beyond). Our narrator—a would-be poet, might-be novelist, actual journalist—keeps bumping up against a senator's son named Trouble.Fear no more the heat o’ the sun,

Nor the furious winter’s rages;

Thou thy worldly task hast done,

Home art gone, and ta’en thy wages:

Golden lads and girls all must,

As chimney-sweepers, come to dust.

Fear no more the frown o’ the great;

Thou art past the tyrant’s stroke;

Care no more to clothe and eat;

To thee the reed is as the oak:

The sceptre, learning, physic, must

All follow this, and come to dust.

Fear no more the lightning flash,

Nor the all-dreaded thunder-stone;

Fear not slander, censure rash;

Thou hast finish’d joy and moan:

All lovers young, all lovers must

Consign to thee, and come to dust.

No exorciser harm thee!

Nor no witchcraft charm thee!

Ghost unlaid forbear thee!

Nothing ill come near thee!

Quiet consummation have;

And renowned be thy grave! (IV.ii.258-81)

Early in the novel, Trouble arrives at our narrator's boarding school. At first, he is wildly popular; he then sinks into the utmost disrepute. In the scene that has the most Shakespeare, Trouble (in disrepute) is one of the boys who are reading out loud from Cymbeline in their English class. Here's the scene (click on the image below to enlarge it and to make it legible):

It isn't much, but it is compelling. And it reminds me of another novel that uses the same song from Cymbeline for its own purposes. Stay tuned!

Tuesday, January 8, 2013

Titus Andronicus and Buffy, the Vampire Slayer

“Normal Again.” By Joss Whedon and Diego Gutierrez. Dir. Rick Rosenthal. Perf. Sarah Michelle Gellar, Nicholas Brendon, and Emma Caulfield. Buffy, the Vampire Slayer. Season 6, episode 17. The WB Television Network. 12 March 2002. DVD. 20th Century Fox, 2010.

While deep in research on adaptations and derivative versions of Titus Andronicus, a careful reader told me to try this episode of Buffy, the Vampire Slayer, a show I had never watched (even though I mentioned it in a presentation on violent female characters in Shakespeare).

She later said (when I had viewed the episode and declared myself unable to find much in the way of Titus-related material) she may have been mistaken.

All the same, I found one quote that might be relevant. Buffy asks the monster that pounces in a question that might easily have been addressed to Tamora in the final scene of Titus Andronicus:

Links: The Episode at IMDB.

While deep in research on adaptations and derivative versions of Titus Andronicus, a careful reader told me to try this episode of Buffy, the Vampire Slayer, a show I had never watched (even though I mentioned it in a presentation on violent female characters in Shakespeare).

She later said (when I had viewed the episode and declared myself unable to find much in the way of Titus-related material) she may have been mistaken.

All the same, I found one quote that might be relevant. Buffy asks the monster that pounces in a question that might easily have been addressed to Tamora in the final scene of Titus Andronicus:

Links: The Episode at IMDB.

Monday, January 7, 2013

Shakespeare in Huckleberry Finn (The 1939 Film with Mickey Rooney)

Huckleberry Finn. Dir. Richard Thorpe. Perf. Mickey Rooney, Walter Connolly, and William Frawley. 1939. DVD. Warner Brothers, 2009.

Back in May of 2012, I wrote about some of the Shakespeare in Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn and a bit of that that made its way into a 1955 film version of the novel (for which, q.v.).

A little while later, I tracked down the 1939 film—the one with Mickey Rooney as Huck—and found a great deal more Shakespeare in it. I prepared a clip, uploaded it to the blog, and promptly forgot all about it.

But my forgetfulness is your (eventual) gain! Here's the clip:

I find that delightful. And I'm impressed by the playbill, too. Imagine being able to see David Garrick and Mrs. Siddons play these roles—fifty years or so after they died. Please note, also, the line that declares "Ladies & Children Not Admitted." Perhaps I should have mentioned that earlier in this post. I apologize if any Ladies or Children have been offended.

Links: The Film at IMDB.

Back in May of 2012, I wrote about some of the Shakespeare in Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn and a bit of that that made its way into a 1955 film version of the novel (for which, q.v.).

A little while later, I tracked down the 1939 film—the one with Mickey Rooney as Huck—and found a great deal more Shakespeare in it. I prepared a clip, uploaded it to the blog, and promptly forgot all about it.

But my forgetfulness is your (eventual) gain! Here's the clip:

I find that delightful. And I'm impressed by the playbill, too. Imagine being able to see David Garrick and Mrs. Siddons play these roles—fifty years or so after they died. Please note, also, the line that declares "Ladies & Children Not Admitted." Perhaps I should have mentioned that earlier in this post. I apologize if any Ladies or Children have been offended.

Links: The Film at IMDB.

Friday, January 4, 2013

Gregory Doran's African Setting of Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar. Dir. Gregory Doran. Perf. Segun Akingbola, Adjoa Andoh, Theo Ogundipe, and Mark Ebulue. 2012. DVD. Illuminations, 2012.

This film, available to UK markets (click here, for example) but not yet available in the US, intriguingly sets Julius Caesar in contemporary Africa. Although none of the things I've read about the production place it more specifically than that, I would hazard Nigeria as the country inspiring the setting—many of the actors' names are Nigerian, as are some of the accents.

Many of the film's scenes are enacted on the Royal Shakespeare Company's stage, but other scenes are shot in a studio—and the description the UK branch of Amazon gives notes that it was also filmed "on location." The result is an excellent mix of theatre and film. In other words, don't expect this to be merely a filmed version of a stage production. Even the camera work for the on-stage scenes is varied and impressive.

As a sample, here's part of the opening scene. After much ceremony and celebration, Julius Caesar gives instructions to Mark Antony that humiliate Calpurnia—after which, he hears the voice of the Soothsayer over the noise of the crowd.

I have not watched the entire film—I wanted to get some preliminary impressions out quickly—but I'm enormously impressed. I admire the choices regarding the Soothsayer: instead of a weak, old man—blind in some productions (e.g., Mankiewicz's)—this is a strong, powerful Soothsayer, not easily dismissed.

Links: The Film at IMDB.

This film, available to UK markets (click here, for example) but not yet available in the US, intriguingly sets Julius Caesar in contemporary Africa. Although none of the things I've read about the production place it more specifically than that, I would hazard Nigeria as the country inspiring the setting—many of the actors' names are Nigerian, as are some of the accents.

Many of the film's scenes are enacted on the Royal Shakespeare Company's stage, but other scenes are shot in a studio—and the description the UK branch of Amazon gives notes that it was also filmed "on location." The result is an excellent mix of theatre and film. In other words, don't expect this to be merely a filmed version of a stage production. Even the camera work for the on-stage scenes is varied and impressive.

As a sample, here's part of the opening scene. After much ceremony and celebration, Julius Caesar gives instructions to Mark Antony that humiliate Calpurnia—after which, he hears the voice of the Soothsayer over the noise of the crowd.

I have not watched the entire film—I wanted to get some preliminary impressions out quickly—but I'm enormously impressed. I admire the choices regarding the Soothsayer: instead of a weak, old man—blind in some productions (e.g., Mankiewicz's)—this is a strong, powerful Soothsayer, not easily dismissed.

I hope this production will soon become more widely available. It's enormously enjoyable as a production of Julius Caesar, and its position in Global Shakespeares will provide a significant amount of food for thought.

Links: The Film at IMDB.

Click here to purchase the film from amazon.co.uk