Der Kaufmann von Venedig. Von William Shakespeare. Various performances. Various locations. Various purposes.

When I title this post "

The Merchant of Venice in Nazi Germany," I'm not talking about a performance staged as if it were in Nazi Germany. I'm talking about performances of the play that were actually produced under that horrible regime during a terrible point in human history.

Years ago, I heard somewhere that a radio performance of Merchant was broadcast on the night before Kristallnacht with the intent of being incendiary enough to heighten the violence of that night (Note: That turns out not to have been accurate, and we'll come back to that later). It struck me as odd. How could a play that has the potential for such sympathy for the Jewish people ("Hath not a Jew eyes?") be performed so close to an event that was so detrimental for the Jewish people?

That nagging question began a long period of (admittedly on-and-off) research. Some of these notes have been around since well before the pandemic. But now, after doing quite a bit of research, I have some answers—but some questions remain.

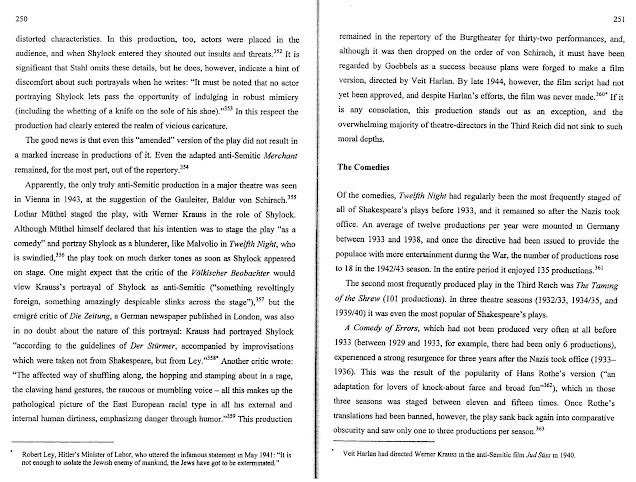

I started my research with Rodney Symington's The Nazi Appropriation of Shakespeare: Cultural Politics in the Third Reich (Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 2005). From Symington, I learned that Shakespeare in general was used for Nazi propaganda, but that Merchant, despite the possibilities for playing Shylock in an unsympathetic, anti-semetic light, was not often performed from 1933 to 1944. Symington shows that the number of performances over those years decreased, and he explains some of the reasons why:

Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice, then, had to be altered significantly to suit the Nazi agenda—and even then, it was more problematic than successful.

The decline in productions of Merchant is confirmed by Andrew G. Bonnell in Shylock in Germany: Antisemitism and the German Theatre from the Enlightenment to the Nazis (London: Tauris Academic Studies, 2008). He notes that "Producers of the play in the 'Third Reich' were also confronted with a number of difficulties: Shylock is given the opportunity to humanize himself ('Hath not a Jew eyes? hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? . . .'); the union of Lorenzo, a Christian, and Jessica, Shylock's daughter, constituted an offence against the 1935 Nuremberg Laws; and there was the 'danger' noted by Elisabeth Frenzel, that an audience might feel some pity for the defeated and abjectly humiliated Shylock" (144).

Bonnell also tells us what I ought to have suspected: Shylock's "Hath not a Jew eyes?" speech is cut completely from (it's implied) all these productions.

In addition, Bonnell provides some commentary on

Kristallnacht and performances of

The Merchant of Venice. To give that some context,

Kristallnacht was on the night of November 9 and the morning of November 10, 1938. It involved orchestrated violence against Jewish businesses, homes, and places of worship. You can read more about

Kristallnacht here.

Bonnell's research describes a theatre production of Merchant that "celebrated Kristallnacht" and that there was a radio production of the play about a month after Kirstallnacht (150):

As I worked to confirm or deny what I'd heard—that a radio broadcast of Merchant was broadcast before Kristallnacht in order to encourage the violence of Kristallnacht—I found the performance of 15 December 1938 (five weeks after Kristallnacht) to be the closest.

But then I started to find it hard to confirm that performance. In Social Shakespeare: Aspects of Renaissance Dramaturgy and Contemporary Society (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1995), Peter J. Smith writes "Shortly' after Kirstallnacht in 1938, The Merchant of Venice was broadcast for propagandistic ends over the German airwaves'" (153), and his citation for that quote is page 23 James Shapiro's Shakespeare and the Jews. After searching Shapiro's 1997 book with that title (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997) and finding nothing on page 23 or anywhere else (a search of an electronic text of the book found no uses of "Kirstallnacht" at all), I started to wonder whether I was finding evidence of a rumor. But I looked at Smith's citation one more time and found that it actually referred to James Shapiro's Shakespeare and the Jews (the twenty-four page printed version of the Parkes Lecture at the University of Southampton in 1992, not the 1997 full-length book).

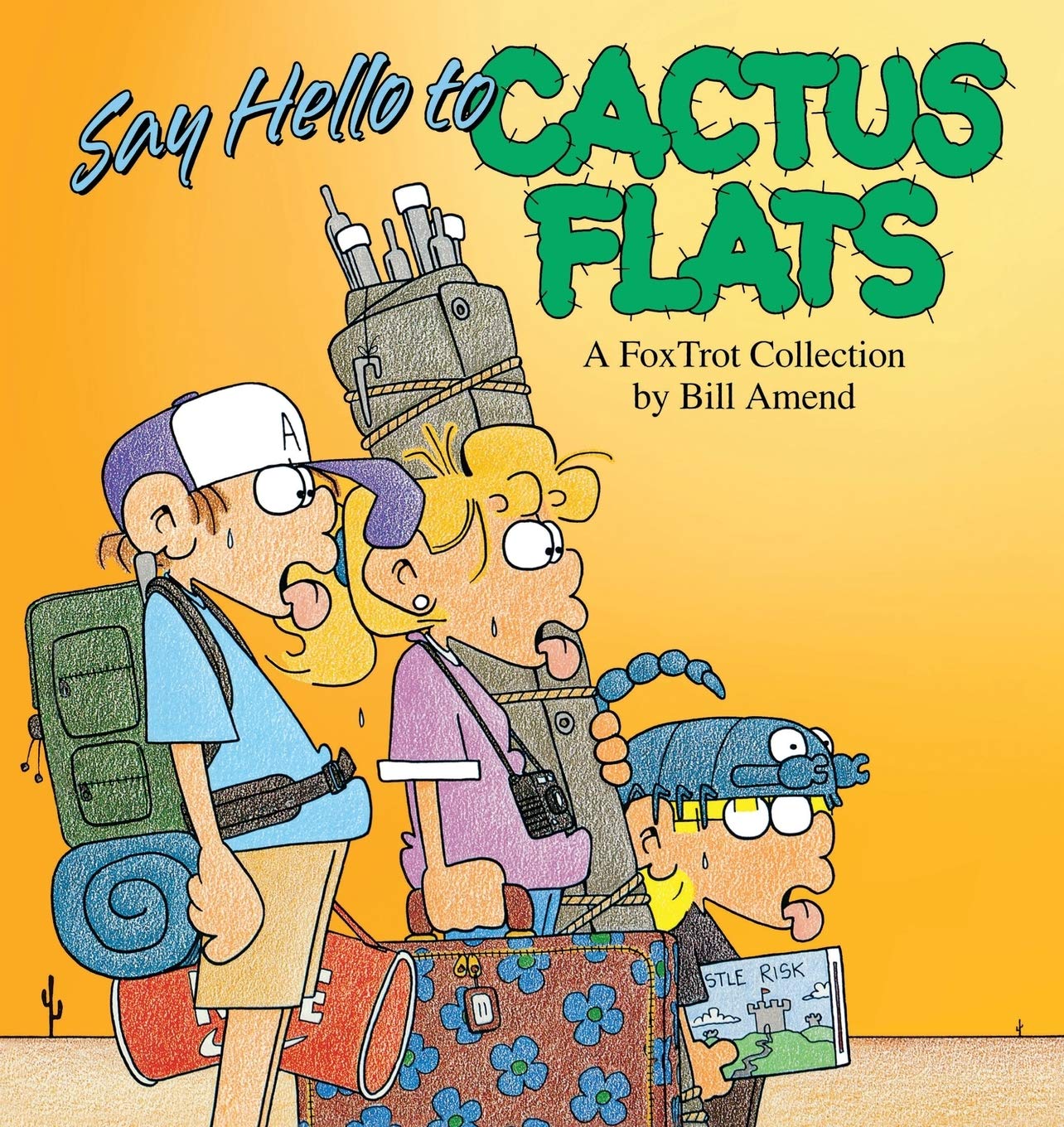

That was better, but the lecture, being a lecture, doesn't offer bibliographic support for its claims. I didn't want to doubt an undoubted authority, but I wanted more than the lecture offers, which is this:

[Note: Markings and emphasis not my own. Highlighting a library book is troublesome enough—but that color? Egad.]

Shapiro is great, and he makes his point (although, as we've seen, productions of Merchant of Venice in Nazi Germany decreased during that period), but I wanted to know the details of that radio broadcast. My research had made it clear that the broadcast wasn't before Kirstallnacht as an incitement to riot but after Kirstallnacht—and far enough after to make the connection more tenuous than related.

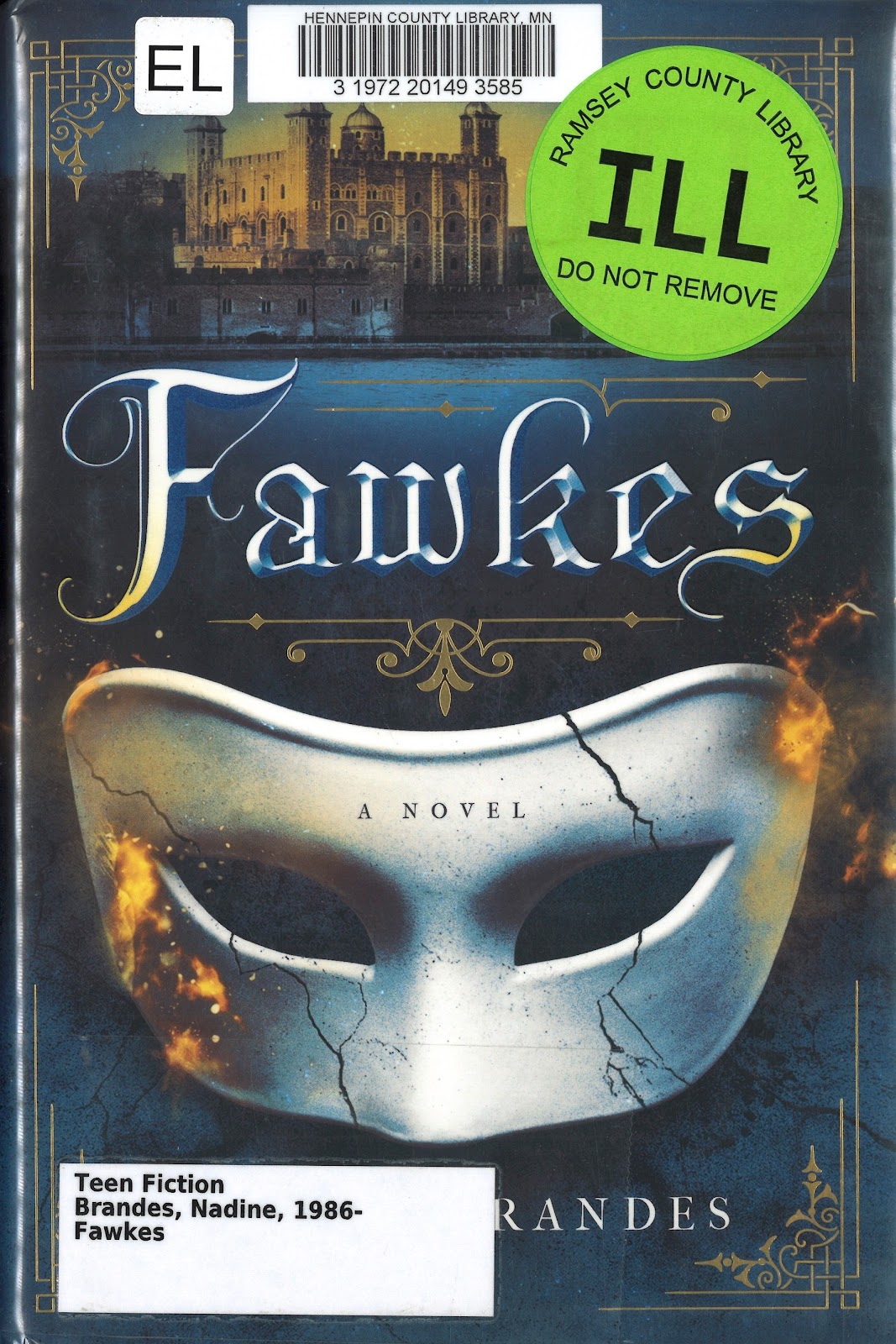

Back, then, to Andrew G. Bonnell's Shylock in Germany I went. His footnote 179 on the page provided above took me to two pages in two separate years of Shakespeare-Jahrbuch. With the help of our magnificent reference librarians, I was able to see one of these: Shakespeare-Jahrbuch 76 (1940): 247. [Note: The footnote points to p. 259, but I haven't yet been able to track down that page.] [Update: page 259 contains a list of plays—see the image at the end of this post.] This part of the research was fun because I don't speak or read German. However, searching through the document for the underlined parts, I found that I could make out some of them. Sommernachtstraum was pretty probably Midsummer Night's Dream (Germans sometimes have one word for things that take four or five in English). And once I knew what Maẞ was (it's short for Maßeinheit, which means "unit of measurement"), I could figure out Maẞ für Maẞ. The "nichts" part of Viel Lärm Um Nichts helped me get to Much Ado About Nothing and Was Ihr Wollis seemed to be the subtitle of Twelfth Night. And then I got to Kaufmann von Venedig. I remembered the Danish port Kjøbmandehavn from some History of English lectures. So now I knew what to look for.

And here's what the article offered on page 247:

I have some German-speaking friends, and one of them paraphrased the main part of that in this way: "It’s saying the director’s choices were to make Shylock less conspicuously Jewish (blend in more with the whole ensemble/troop), and shift the tone of the performance back towards comedy."

First, I'm always happy to make a new German-speaking friend, so if you have an alternate translation, please let me know! Second, I think that's fascinating, and it's not something addressed by the other scholarly work I've read. A production of Merchant of Venice performed under Nazi Germany sought to make Shylock less Jewish.

The research has been gradually rolling in, and I've just laid eyes on Shakespeare-Jahrbuch 75 (1939): 198. This is where we learn the details of the radio broadcast entitled "Das Urteil" ("The Judgement"):

And there, for now, the research ends. I don't believe any production of

Merchant of Venice directly stirred up the riotous actions of

Kirstallnacht; nor do I think any production rode on its coattails to confirm its faulty, anti-semitic justification. The five-week gap seems more coincidental that intentional.

I didn't find what I expected, but this research journey has been fascinating and enlightening.

Bonus image: Shakespeare-Jahrbuch 76 (1940): 259.