Kiss me, Kate. Dir. George Sidney. Perf. Kathryn Grayson, Howard Keel, and Ann Miller. 1953. DVD. Warner Home Video, 2003.

Kiss me, Kate. Dir. George Sidney. Perf. Kathryn Grayson, Howard Keel, and Ann Miller. 1953. DVD. Warner Home Video, 2003.

Cole Porter's lyrics—hot at the time, even hotter (in some cases) now—are frequently edited for performance. For example, the lyrics of "I Get a Kick out of You" are often changed. We no longer hear performers sing this:

Some get a kick from cocaine.

I'm sure that if

I took even one sniff

It would bore me terrif-

ically, too.

Yet I get a kick out of you.

Instead, they often sing the following:

Some like a bob-type refrain.

I'm sure that if

I heard even one riff

It would bore me terrif-

ically, too.

Yet I get a kick out of you.

The original opening lines of "Let's Do It (Let's Fall in Love)" are even more objectionable. I decline to quote the original lyrics, in fact—they are disgustingly racist.

Those lyrics are so seldom performed that I was amazed and appalled to hear Peggy Lee singing them on an early recording with Benny Goodman.

The 1953 movie version of

Kiss me, Kate alters the lyrics considerably—both in major ways (as in "Always True to you (in my Fashion)," where Lois and Bill share the new lyrics) and in minor ways (as in the prefatory verses to "Tom, Dick, or Harry"). Over all, the changes seem to be intended to soften Porter's risqué lyrics.

In "Always True," for example, Bill sings these words to Lois:

Saw you out with Mr. Fritz.

You were dining at the Ritz!

To which she replies:

Mr. Fritz invented Schlitz, and Schlitz must pay

But I'm always true to you, darling, in my fashion.

Yes, I'm always true to you, darling, in my way.

The director, producer, and / or the writer could have stuck with Porter's original lyric (all sung by Lois):

From Milwaukee, Mister Fritz

Often moves me to the Ritz.

Mister Fritz is full of Schlitz and full of play.

But . . .

[In other recordings, "moves me to" is frequently replaced with "dines me at" from the same risqué-reduction motives.]

The decision to alter ribald lyrics is carried through with some consistency. In "Tom, Dick, or Harry," Hortensio sings "To give a social lift to thy position, / Marry me, marry me, marry me." Apparently, the original words (" To give a social goose to thy position") might have been objectionable.

The fact that such a mildly-objectionable phrase was altered makes it all the more surprising that these lines from "Brush up your Shakespeare" are left intact. A number of verses are eliminated or altered ("If her virtue, at first, she defends—well, / Just remind her that All's Well that Ends Well" is changed to "And if still to be shocked she pretends—well / Just remind her that All's Well that Ends Well"), but why did they decide to retain this one?

If she fights when her clothes you are mussing . . .

What are clothes? Much Ado About Nussing!

If she says your behavior is heinous,

Kick her right in the Coriolanus.

They felt they couldn't get away with "goose," but "Coriolanus" presents no difficulty?

Perhaps they felt that a line like that was suited to the gangsters who sing it but that the "goose" line wasn't appropriate to one of Bianca's suitors. Perhaps.

Or perhaps the indecency level of "goose" has decreased while that of the other line has increased.

For more about Cole Porter's lyrics, go to Google Books, which has

The Complete Lyrics of Cole Porter as a

searchable electronic text. It's quite an amazing resource.

Finally, as a reward for coming this far back in the archives, I’m providing a clip from the film! This indicates that this blog post has been revised some time after its initial composition. Congratulations!

Links: The Film at IMDB.

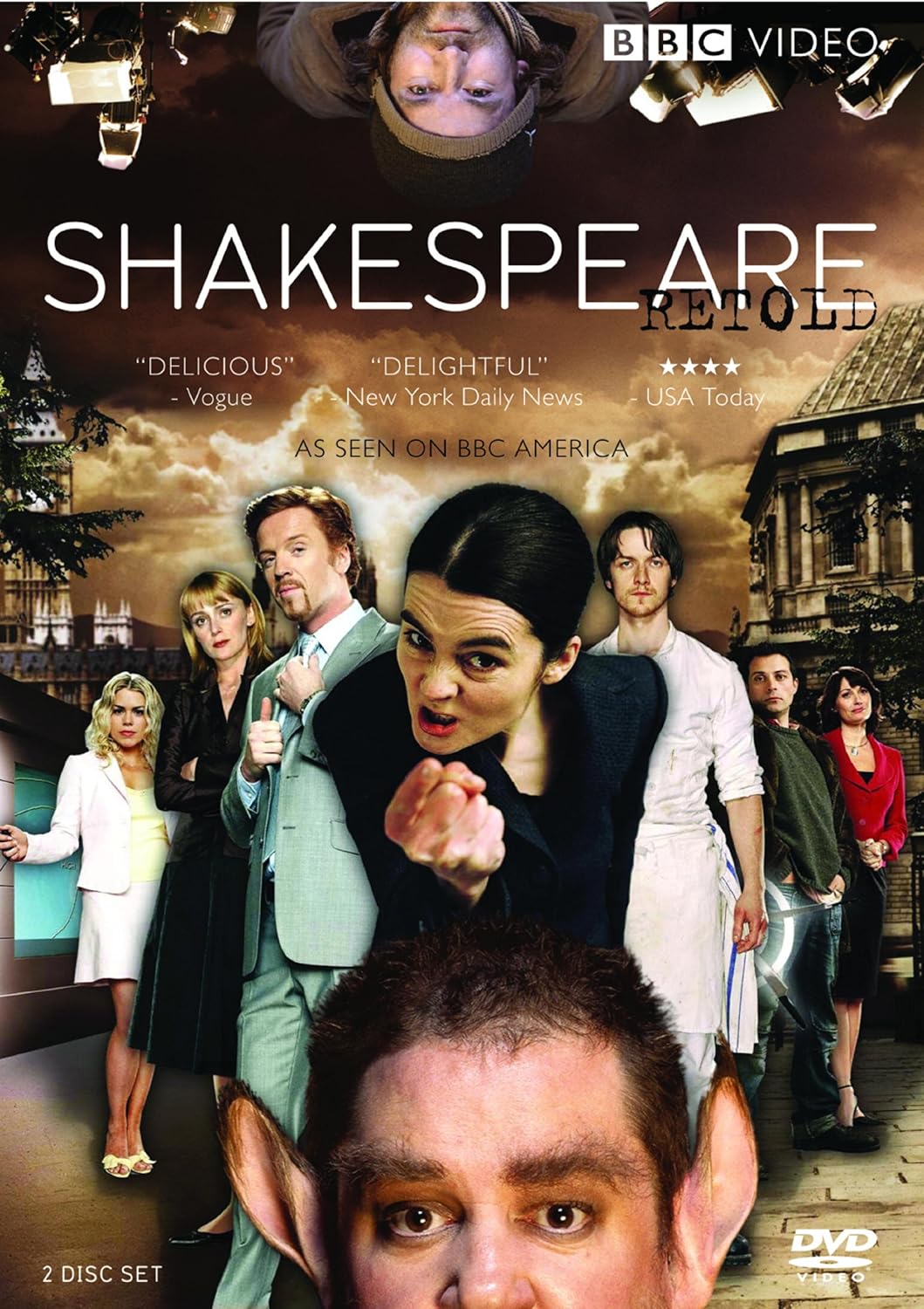

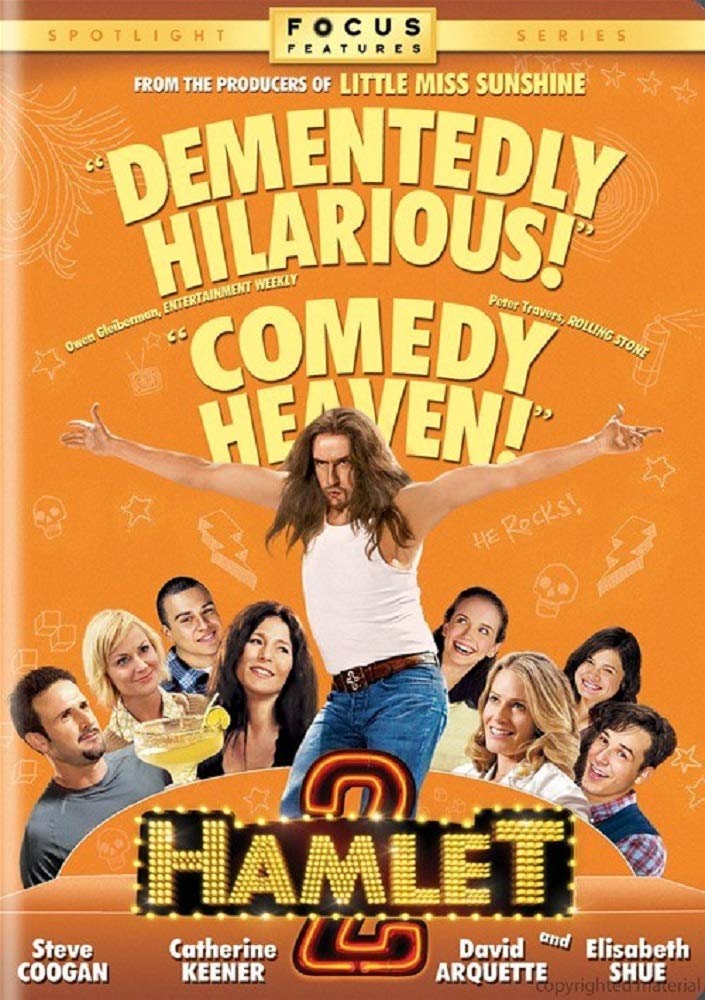

Click below to purchase the film from amazon.com

(and to support Bardfilm as you do so).

“The Taming of the Shrew.” By Christopher Lloyd. Perf. Tim Daly, Steven Weber, and Crystal Bernard. Dir. Andy Ackerman. Wings. Season 3, episode 3. NBC. 10 October 1991. DVD. Paramount, 2006.

“The Taming of the Shrew.” By Christopher Lloyd. Perf. Tim Daly, Steven Weber, and Crystal Bernard. Dir. Andy Ackerman. Wings. Season 3, episode 3. NBC. 10 October 1991. DVD. Paramount, 2006.

.png)